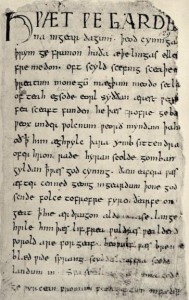

Speaking of translating Tolkien’s world to TV and cinema, we dug into our archives to find a rather relevant masterpiece from Green Books staffer Ostadan – originally posted November 4th, 2004. Enjoy!

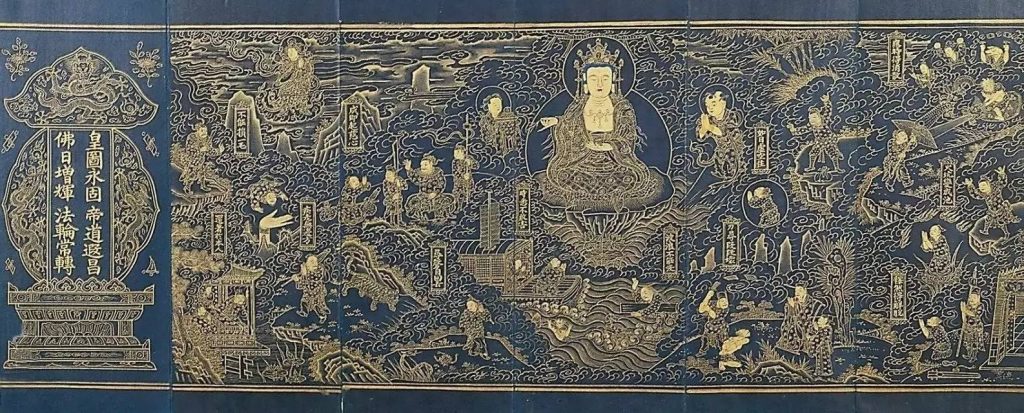

“Translation is like chewing food that is to be fed to others who are unable to chew themselves. As a result, the masticated food is bound to be poorer in taste and flavor than the original.” [attributed to Kumarajiva, translator of Buddhist texts into Chinese. Translated.]

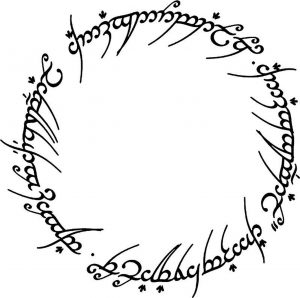

In the article Glossopoeia for Fun and Profit, we saw the Esperanto translation of the Ring inscription:

Unu Ringo ilin regas, Unu ilin prenas,

Unu Ringo en mallumon ilin gvidas kaj katenas.

Let us look at this translation more carefully. If we were to take each word and translate it to English directly, it would read,

One Ring them rules, One them takes,

One Ring into darkness them guides and chains.

Esperanto’s word order is more liberal than English, especially in verse; a more grammatically correct English translation would be “One Ring rules them, One takes them, One Ring guides them into darkness and chains them.” Those familiar with the English text will see many evident differences — the use of present tense; the reduction of “them all” to simply “them”; the change of “find” to “take”, and so on. Why should this be so? The main reason is that Bertil Wennergren, who translated the verse, was attempting to retain not only the sense of the text, but the rhyme scheme and general meter of the original. Esperanto, which uses suffixes as markers for such things as tense and part of speech, has few single-syllable words. In contrast, there is only one word of more than one syllable, “darkness”, in the entire English version of the Ring couplet (and few, indeed, in the entire Ring-verse). If any semblence of the poetry of the original is to be retained, then the meaning of the text must be altered somewhat to fit the restrictions imposed by the verse form and the language of translation.

Of course, within the story, the famous couplet is itself only a translation, with a slight change in meter, of the Black Speech found on the Ring:

Ash nazg durbatulūk, ash nazg gimbatul,

Ash nazg thrakatulūk, agh burzum-ishi krimpatul.

Gandalf says that his rendering in the Common Speech is “close enough” to what is said on the Ring. So the question arises: is the Esperanto translation similarly “close enough”? A “purist” might say, no: there are too many details lost or even changed by this translation, and Tolkien’s linguistic work has been undermined; someone reading the Esperanto text would come to very different conclusions about the vocabulary and grammar of Black Speech from those reached by English-speaking readers. But someone of a more “revisionist” bent sould say that the Esperanto Ring-inscription tells, probably as well as possible given the constraints of a verse translation in Esperanto, the same story as the original English. After all, it is certainly plausible that Celebrimbor, hearing these words spoken from afar as Sauron first took up the One Ring, would indeed know just how he had been betrayed and what Sauron’s true purpose behind the Rings of Power was.

In a real sense, any translated work is a collaborative effort between the original author and the translator, much as a symphonic performance is a collaboration between the composer and the conductor. In a work as complex as The Lord of the Rings, the translator must be aware of the stylistic and linguistic techniques that Tolkien is using, and create them anew in the language of translation. For the result to have any artistry at all, the translator has to be as creative and capable in the language of translation as Tolkien was in his own. The result will not be pure Tolkien; it will be Tolkien as interpreted and re-told by the translator. Arden Smith’s irregular column in the journal Vinyar Tengwar, entitled “Transitions in Translations”, has documented a wide range of successful and unsuccessful translations. In some, little care is taken in style or nomenclature — one might be reminded of the infamous Japanese subtitles for the Fellowship of the Ring movie. In others, the translator may go as far as inventing Tengwar and Cirth modes for the language of translation and will re-draw the title page inscription in translation, as well as re-lettering the translation of the West-gate of Moria in the illustration. But in all cases, the result is not, and cannot be, identical to the experience of reading the original English text.

A “purist” might therefore conclude that because a translation necessarily loses some of the nuances and richness of the original, nobody should read Tolkien’s work in translation, and that the translators themselves are wasting their time in a futile exercise at best, or a fraudulent representation of their own works as being J.R.R. Tolkien’s at worst. To the purist, Tolkien’s original work is the only “true” account of events in a world that seems nearly as real as the ancient history of our own world, and deviation from that account seems to be somehow a distortion of a primary truth. But most people would agree that, given a certain minimum quality of translation, the defects inherent in reading a work in translation are outweighed by the availability of the book to people who cannot read it in English and would not be able to experience Middle-earth in any form without the translation, like the unfortunate soul in the quotation from Kumarajiva, who requires someone else to chew their food if they are to avoid starvation. Some of these people may even be motivated by a good translation to search out an English edition and laboriously work through it.

By now, the reader has probably anticipated the author’s conclusion from these musings about translation: the art of the filmmaker has much in common with the art of the translator. The requirements of film — or at least an artistically and commercially successful one — dictate particular rhythms and modes of expression in the storytelling that the original author contemplated no more than Tolkien considered how the Ring-verse would fit the rhythms of Esperanto or other languages. Even more than a translator, the filmmaker is a collaborator with the author, reinventing and recreating the author’s work so that it can be expressed as artistically as possible in the “language of film”. The result will not be purely Tolkien’s work, and will inevitably lose much of the delicious “flavor” of the original. It may even have serious defects in several particulars; but the real question is whether, like the Ring-verse translation, it tells the same essential story, “close enough”. If it does, then it does what any good translation does: it brings a great work to people who otherwise would not read it on their own.

“I cannot read the black and white letters,” he said in a quavering voice.

“No,” said Jackson, “but I can. The letters are English, of a narrative mode, but the language is that of the Epic Romance, which I will not utter here. But this in the Cinematic Tongue is what is said, close enough…”

(Fade to black. Music up.)

– Ostadan