Continuing a series of articles from our international fan-base, contributor and TORn TUESDAY friend Tedoras brings us a thorough look at the most bemusing/amusing character in all of Tolkiens’ legendarium: the master of the Old Forest himself, Tom Bombadil.

Tom Bombadil – Master and Mystery

By Tedoras

Mention the name of Tom Bombadil around Tolkien fans and you are likely to spark a debate: a debate which, in Tolkien fandom, remains one of the most controversial and longest-argued of them all. This is perhaps because even the most fundamental questions surrounding Tom Bombadil are hard to answer; certainly, he is the most enigmatic character in The Lord of the Rings. Because of his uncanny nature, Tom Bombadil remains unique among all of Tolkien’s characters: as readers, we have the same understanding of him today as readers did when they first discovered him—that is to say, while scholarly works on Aragorn and Frodo abound, we are no closer to uncovering the true Tom Bombadil today than we were almost sixty years ago. In writing this article, I hope to accomplish a few goals: first, to present a thorough character study of Tom Bombadil (i.e. to lay out what we know); second, to discuss the main or popular theories in the debate (i.e. to lay out what we think); and third, to draw a conclusion (or, rather, an inference) as to the true nature of Tom Bombadil. Whether you are a veteran of this debate or are just now being exposed to it, I hope you will join me on a journey of herculean proportions to answer the most testing of all questions: who (or what) is Tom Bombadil?

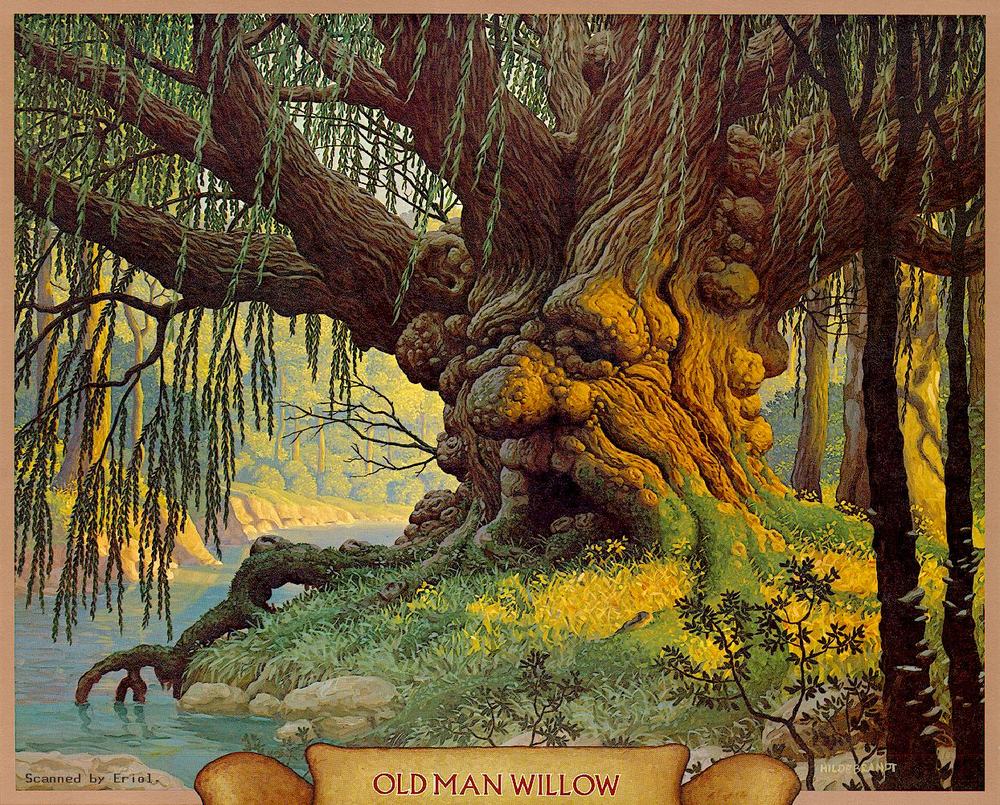

As Saruman coldly says in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey: “Let us examine what we know.” Well, in this instance, that is very apt advice, indeed. Tom Bombadil, as many of you already know, stumbles upon the hobbits in the Old Forest in September of the Third Age 3018; he proceeds to rescue them from Old Man Willow, and then brings them along to his home deep in the Forest where he lives with his (also rather enigmatic) wife Goldberry. Tom is marked throughout these episodes with a light and cheery tone: from his colorful attire to his seemingly continual singing (and his ring a dong dillo’s). Yet Tom’s light-hearted nature—while ostensibly unwarranted, considering where he lives—is, in fact, well-attributed: he is a very, very old and wise man (or rather, being that looks like a man). We will, in time, return to look more closely at the importance and uniqueness of Tom’s personality, but for now, let us focus on his age.

Readers quickly become aware that Tom is a special character, even from our very first meeting with him. One of the reasons for this is his fantastic age. And while it may not surprise us that Tom is indeed old, just how old may. Frodo, who appears just as confused about Tom as we are as readers, asks him repeatedly, “Who are you?” (Tolkien 129). Tom replies that he is “eldest,” and then he proceeds to explain:

“Tom was here before the river and the trees…He made paths before the Big People, and saw the Little People arriving…When the Elves passed westward, Tom was already here, before the seas were bent…before the Dark Lord came from Outside.” (129)

“Tom was here before the river and the trees…He made paths before the Big People, and saw the Little People arriving…When the Elves passed westward, Tom was already here, before the seas were bent…before the Dark Lord came from Outside.” (129)

Since Tom’s own information is arguably the most accurate about him, let us use the above quotation to determine just how old he is. First, we know Tom has lived in Arda since “before the river and the trees,” a reference to the Spring of Arda. The Spring of Arda is the period from 1900 to 3450 (in Valian Years, not solar years, mind you—though we will return to this soon) of the Years of the Lamps, in which the world was populated with living things. Secondly, he has been in Middle-earth since year 1 of the First Age, when Men awoke; additionally, he saw the hobbits migrating west around T.A. 1300. Tom also saw the Elves pass west: this refers to the Sundering of the Elves and, more precisely, to the First and Second Sunderings in the Years of the Trees 1105 and 1115, respectively. The “seas were bent” in F.A. 587 following the War of Wrath. Most interestingly, though, is that Tom was in Arda before Morgoth (and, in turn, all the Valar) came there during the First War, from year 1 to about 1499 of the Years of the Lamps. Thus, we know that Tom Bombadil was one of the first—if not the very first—inhabitants of Arda following the Music of the Ainur and the creation of Eä.

Now, knowing that Tom has existed (it is, as yet, impossible to say that he was born or created, or even that he entered Arda) since year 1 of the Years of the Lamps, we can calculate his exact age. We must note, however, the sort of ripple that exists in time in Tolkien’s works: each year in the Years of the Lamps and Years of the Trees is a Valian year (about 9.582 solar years). The First Age, with the rising of the Sun, marks the use of solar years in counting. So, we can use the range from 1 Years of the Lamps to T.A. 3018 (when Tom meets the hobbits) to calculate his age. We simply multiply 3500 (the number of Valian years in the Years of the Lamps) by 9.582 (3500 x 9.582 = 33,537), repeat this process for the Years of the Trees (~1500 x 9.582 = 14,373), and add the total number of solar years from all the Ages up until T.A. 3018 (590 + 3,441 + 3018 = 7049). So, by T.A. 3018 Tom Bombadil is already some 54,959 (solar) years old!

Beyond his age, Tom is characterized by a few other unique traits. First is his reaction (or lack thereof) to the Ring. “Show me the Ring!” he says to Frodo, who, surprisingly, hands it right over without any qualms (much in contrast to the very protective, hesitant Frodo we see later on). Tom proceeds to “put it to his eye and laugh[s]” (130). Yes, the reaction of Tom Bombadil to the One Ring, the most powerful and dangerous object in the world, is laughter—not worry nor despair, and certainly not fear. Then, when Tom puts the Ring on his finger, there is “no sign of [him] disappearing” (130). And how does Tom react to this instance? You’ve got it right: he laughs and, to further show how little he cares for the Ring, he does what appears to be a little sleight of hand with it before returning it to Frodo “with a smile” (130).

Not only is Tom unaffected by the Ring himself, but he notices its effects on others. When Frodo slips on the Ring (to check that is, in fact the Ring after lending it to Tom), Tom immediately notices the invisible hobbit sneaking off:

“‘Hey there!’ cried Tom, glancing towards [Frodo] with a most seeing look in his shining eyes. ‘Hey! Come Frodo, there! Where be you a-going? Old Tom Bombadil’s not as blind as that yet. Take off your golden ring!” (131)

Clearly, Tom is unaffected, personally or otherwise, by the Ring. And he is the only character in the whole of the novel to have this ostensible immunity to the Ring. It is certainly a powerful being that holds this trait.

Yet what do we typically associate with power and wisdom? Perhaps visions of age-worn, rather tough and callous individuals spring to mind—yet this is not the case with Tom Bombadil. As I noted before, Tom has a rather affable, light-hearted personality. He is certainly not a man of affectation: no matter the circumstance nor the people involved, Tom is always in a joyous mood, singing and bouncing around (or at least disposed to do so). Tom is so happy-go-lucky because he has no concept of fear. Take the following examples: (1) he rescues the hobbits from the clutches of Old Man Willow as if he were reprimanding a child, not challenging a great evil; (2) he lives in the Old Forest, a place ripe with fearful beasts and about which tales of fright abound; (3) he saves the hobbits from a barrow-wight, coming with song and a spring in his step to one of the most dreadful and dangerous mishaps in the story. Take this quotation from “Fog on the Barrow-Downs,” for example:

“’You won’t find your clothes again,’ said Tom, bounding down from the mound, and laughing as he danced round them in the sunlight. One would have thought that nothing dangerous or dreadful had happened; and indeed the horror faded out of their hearts as they looked at him, and saw the merry glint in his eyes.” (140)

It is plain to note: where others would fear, Tom Bombadil does not. It is not even that Tom is simply not afraid, nor that he has overcome his fear; rather, he has no concept, no idea whatsoever, of fear. He is entirely composed of the good-natured, light-hearted fibers that render him capable of laughing in the very face of the One Ring.

It is plain to note: where others would fear, Tom Bombadil does not. It is not even that Tom is simply not afraid, nor that he has overcome his fear; rather, he has no concept, no idea whatsoever, of fear. He is entirely composed of the good-natured, light-hearted fibers that render him capable of laughing in the very face of the One Ring.

And this lack of fear (especially with regards to the Ring) is unique. Gandalf certainly shows a sense of fear on many occasions: from his fear of entering Moria, to his fear of the Ring and the Enemy. Galadriel and Elrond both fear the Ring, for in either using it or keeping it hidden they know it will bring about their ruin. Even the Enemy is not free from the grasp of fear: when he learns of Aragorn’s return and the possibility of united opposition to him, Sauron begins to feel afraid. While the fear that all of these characters experience may differ in many ways, fear it is nonetheless. And it is exactly this sense of fear that Tom Bombadil does not possess.

There remains now just one last point regarding Tom’s character that I believe is worth noting: his repeated association with the earth. Frodo, the night the hobbits spend in Tom Bombadil’s house, has a vivid dream of

“a song that seemed to come like a pale light behind a grey rain-curtain, and growing stronger to turn the veil all to glass and silver, until at last it was rolled back, and a far green country opened before him under a swift sunrise.” (132)

This dream—a clear reference to Valinor—is interrupted: Frodo awakens to see “Tom whistling like a tree-full of birds” and he notes “the sun was already slanting down the hill…Outside everything was green and pale gold” (132). Here, we note Tom’s stark association with the earth or, perhaps more prominently, his dissociation from Valinor. Tom interrupts this dream (in essence, the thought that he may be associated with Valinor), and he immediately brings Frodo back to the earth: to the birds, trees, and green of the living, mortal earth. The notion that Tom is more an earthly, temporal being is quite important: it is vindicated by what we have learned of his age, and it will greatly help us in deciding what Tom is and isn’t.

Knowing what we do about Tom Bombadil now, we can move on to the second half of this task: discovering who Tom truly is. We will be looking at the main and other popular theories of this debate, and one by one, we will see which, if any of the pre-proposed categories, Tom fits. After thoroughly examining all options, then—and only then—will we be able to make a final conclusion. (And, if we are lucky, such a conclusion may not be that we will simply never know the answer.)

Is Tom…

A Man, Elf, Hobbit, Dwarf, etc?

Tom is decidedly not a member of any of the races or kindreds of Middle-earth. We can most certainly eliminate him from all such groups (especially from Men and Elves, which would be the two most likely groups) by noting his age (i.e. he was around before them), his physical characteristics (size, beard, etc.), and how the Ring does not affect him.

A Vala?

It is certainly difficult to claim that Tom is one of the great Powers of the World for many reasons. First, all fourteen of the Valar are accounted for, and Tom is not named among them. Second, as we noted before, Tom was living in Arda before the Valar (led by Morgoth) entered the world. Third, Tom refers to himself as “Eldest,” a title to which all the Valar are beholding, not just he (if indeed he were a Vala). Lastly, we know that Tom calls Morgoth “the Dark Lord” (as quoted above). It is hard to imagine any of the Valar referring to their greatest rival, the embodiment of Evil, by this name: certainly, the Valar reserved such reverence in the title “Lord” for Manwe alone. Additionally, fans over at The Encyclopedia of Arda have noted that characterize we would expect to note that Tom is a Vala (such as Gandalf, one of the Maiar), do not.

A Maiar?

This theory is, in some ways, a rather attractive one. We know, first of all, that not all of the Maiar were named by Tolkien—this, of course, allows for hypothesizing that Tom is indeed one of them. However, some good counterpoints contest this argument. First, Tom is unaffected by the Ring. We know for certain that other Maiar, from Gandalf to Sauron, were affected by the power and draw of the One Ring. Additionally, remember the total lack of a sense of fear we discussed before? Well, a sense of fear regarding the Ring (or its fate, for the Enemy) pervades the Maiar involved with this struggle. Yet such is not the case with Tom. Also, it is interesting to note how these Maiar are all allied, with one side or another, while Tom remains independent from the conflict.

The One?

Some have even pushed the idea that Tom is The One, Eru Ilúvatar. Yet for all the auspicious remarks made about Tom (how he is “eldest,” etc.), this theory does not hold water either. At the Council of Elrond, we learn many of the reasons why this theory is false. Gandalf states that “he cannot alter the Ring itself, nor break its power over others,” a trait that we would assume the mightiest being of them all, the creator himself, would possess (259). Glorfindel also comments on the idea of giving Tom the Ring to keep safe: “in the end, if all else is conquered, Bombadil will fall, Last as he was First” (259). The notion that Sauron and his folk could defeat Eru (indeed, the notion that Eru is even capable of being killed, defeated, or otherwise harmed) seems rather ridiculous. Furthermore, evidence from Tolkien himself puts a final end to this theory: in Letter 181, Tolkien explicitly states that there is no embodiment of Eru, who exists apart from the World entirely.

A Spirit?

In many of his earlier writings on what would become The Silmarillion (as collected by Christopher Tolkien in The Book of Lost Tales), Tolkien had a concept of Middle-earth as much more similar to his idea of Faerie. Originally, many spirits and sprites (of all kinds and names) entered the World just as the Ainur did—and this notion was not entirely lost in the final published form of The Silmarillion. It is an attractive theory (for many reasons) to say that Tom is a sort of spirit.

The best route to take within this theory is to propose that Tom is a “nature spirit” (perhaps even a “Father Nature,” if you like). First, it makes sense that Tom would come from the Music of the Ainur—this is in accord with his inhabiting Arda from the very beginning. Second, the notion that spirits exist in nature is evident in Middle-earth: from Ents to Old Man Willow to the great prevalence of personification, nature is much more “alive” in Middle-earth than we take it to be. As noted before, Tom is starkly associated with nature and the earth. The way he lives so harmoniously with bird and beast (and how he seems to command nature in his dealings with Old Man Willow) certainly supports this theory. Additionally, we know that Tom is not concerned with the Ring (Gandalf notes that “he would not have come” to the Council of Elrond, and we noted before how remains “unallied” despite the times). He, actually, shows a total disconnect from the affairs of all other human-like beings; he is, rather, concerned only with the natural world. Tom’s neutrality greatly parallels the neutrality that we prescribe to nature. Since we, as fans, do accept the existence and the role of Ents such as Treebeard, I believe making the jump from a natural “spirit of nature” to a man embodying the “spirit of nature” is not so difficult nor controversial. Yet still, we must ask ourselves why, then, does the Ring not affect Tom, when it can certainly affect other aspects of the natural order?

An Incarnation of the Music of Ainur?

This theory is rather unique, and more recently developed than the others. Basically, we know that of all the above theories, only the notion that Tom is a “nature spirit” is relatively sound; branching from that theory, a fan known only as “Ranger from the North” developed a theory in which he posits Tom is “the incarnated spirit of the Music of the Ainur.” The “Ranger” notes two flaws with the basic “nature spirit” argument: first, Tom is not most closely associated with nature (he, personally, shows this discord by fighting against Old Man Willow and the darkness of the Forest); second, Tom is, however, associated with song and music throughout (the way in which he fights nature, for example, is with song). So, it is agreed upon by many (and I am of the same opinion) that Tom is, in fact, a spirit (an incarnate/embodiment) of sorts (i.e. that he has some relation to the Music). The question now becomes whether or not you believe he is more closely related to nature or to the Music itself.

“Ranger from the North” makes a stellar case for the latter. First, he works with the evidence from the “nature spirit” theory, showing how entirely probable the existence of other, extraneous spirits/beings is in Tolkien’s cosmology. Second, he shows how Arda itself is not the incarnation of the Music, distinguishing Middle-earth from the means by which it was created. Then, the “Ranger” makes a very clever comparison between Ungoliant and Bombadil: he notes how, since Ungoliant exists in many ways as an incarnation of the discord of the Music, she parallels Tom; these two are, he says, antitheses, and should be considered in the same way. Just as Ungoliant embodies the evil and darkness with which she was made, so too does Tom embody the light and happiness of the source of his creation. The “Ranger,” additionally, notes a detail of paramount importance: Tom’s name is not all it appears. Certainly, we hear “Tom” and think of our odd uncle or younger brother—yet such is not the case, says the “Ranger.” He notes the story of the great gong Tombo in the Unfinished Tales—coincidence that “t-o-m-b-o” are the first six letters of Tom Bombadil? Is it also coincidental that we find yet another association between Tom and music here? I think not.

The “Ranger from the North” has written extensively on his theory, and I seek not to describe all of his arguments. If you would like a much more detailed and thorough examination of the Music of the Ainur theory, I highly recommend reading what the “Ranger” himself has written here: http://www.whoistombombadil.blogspot.com/

So, we have reached the end of our journey through the “Bombadil Problem.” We have examined the arguments, waded through confusion, sorted out messes, and procured evidence. It is, in my opinion, certain that we must continue to think of Tom as unique, that we must give credit to the enigma that he (intentionally) is. The true “Master” here is perhaps the Professor himself: the truly contradictory nature of this enigma—his simplicity in character and simultaneous complexity in literature—was well crafted. The mystery of Tom reaches far back into the deeps of Tolkien’s mythology, and roots may be found stretching back to the Professor’s first tales of Faerie. While the “riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma” that we call Tom Bombadil will continue to challenge us, so too will it excite us. For through continued debate and discussion, we return time and again to the tales and stories we hold so dear, pouring of pages for hours, scouring word-by-word for some secret hint, trying to piece the puzzle back together. We know that the mystery about Tom was intentionally crafted, and that the Professor may have taken the truth about this character and his own motives in designing him to the grave, yet our drive to uncover more about this most enigmatic of beings is not diminished—why? Perhaps it is precisely because of Tom’s nature that we are fascinated by him: in a Middle-earth so divided by light and dark, good and evil (i.e. clear answers to the “who” and “what”), Tom exists as an uncommitted, uncategorized blank slate. He is the one being so open to interpretation, so predisposed to our imagination, so designed for our wondering. It is not surprising that we love Tom so much, that we pursue this debate so tirelessly, because we each craft our very own Tom Bombadil in our minds—and it is the Professor who intentionally left Tom open to such interpretation. Perhaps we can accept that Tom is simply a mystery—though, no doubt, we will continue discussing and searching for the “truth.”

All references to the text from:

The Lord of the Rings by JRR Tolkien, single-volume edition, Houghton Mifflin (HarperCollins), 2001 (1994 edition of the text)

More information about Tom Bombadil, as well as links to other arguments, can be found below: