In his first of many articles for our worldwide community, Tedoras, long-time audience participant on our TORn TUESDAY webcast brings us an illuminating discussion on something that fascinates the inner-linguist in us all: taking the very Euro-centric names and words Tolkien invented and reforming them into other languages! How do foreign-language translators deal with Tolkien’s legendarium? Read on for some keen insights! Take it away, Tedoras….

In his first of many articles for our worldwide community, Tedoras, long-time audience participant on our TORn TUESDAY webcast brings us an illuminating discussion on something that fascinates the inner-linguist in us all: taking the very Euro-centric names and words Tolkien invented and reforming them into other languages! How do foreign-language translators deal with Tolkien’s legendarium? Read on for some keen insights! Take it away, Tedoras….

————————————————————————————-

By Tedoras — special to TheOneRing.net

In recent years, and especially following the release of the first installment of The Hobbit films, Latin America and China have both become major sources of Tolkien fandom. While we often associate the works of Tolkien with the English-speaking world, the international nature of modern Ringerdom cannot be ignored. The Spanish and Chinese-speaking markets have undeniably helped in making An Unexpected Journey the fourteenth highest grossing film of all time. An historical challenge with Tolkien’s works, however, is how best to translate them. Whether in film or literature, translators have struggled and debate for years on how translate the names of people and places without losing the original sound and meaning that the Professor clearly intended. The process of de-anglicizing these nouns is further complicated because not only must English-language etymology be considered, but also that of Middle-earth’s many distinct tongues.

In Middle-earth, we find a strong correlation between sound and meaning that is particularly evident in the context of “soft” or “hard/harsh” names. For example, the word “Shire” conjures up visions of a distinctly British pastoral community — in essence, one notes a favorable and pleasant sense simply from reading the word. In contrast, “Dol Guldur” is composed of hard consonants and more guttural vowels which denote a rather negative air. Another popular theme is the use of alliteration; it is no mere coincidence that Bilbo Baggins lives in Bag End. As you will see, the biggest problem in translating proper nouns is deciding whether to maintain the original sound or meaning intended by the author, when often both cannot be kept.

It just so happens that Chinese and Spanish are two languages I study, so, in homage to the large Latin American and Chinese Tolkien-fan base around the world, I have decided to present some translations of proper nouns from The Hobbit. While these translations certainly highlight the many different ways Tolkien’s works can be translated, they also provide some important insight into Middle-earth (and some unintended laughs along the way).

I first present some Spanish translations of proper names.

These translations reflect an effort to keep the original meaning of a word, rather than its sound. However, because of its close relationship with English, Spanish allows for the pronunciation of many words in their original form.

Bilbo Bolsón

This is of course our favorite hobbit, Bilbo Baggins. Interesting here is the translation of the surname. In Spanish, “bolsón” is the augmentative form of “bolsa,” which literally means “bag.” A “bolsón” is simply a large bag or backpack, yet in translation it is used to convey the “bag” in Baggins.

Bardo el Arquero

Bard the Bowman is, in Spanish, literally Bard the Archer. In this case, we note a loss of alliteration in translation. It may seem trivial, but alliteration very much shapes how we view a character. The strong “b” sound in Bard’s English title provides him with a bold, confident aura. In a way, the Spanish version tries to make up for this loss by means of assonance and the repetition of the “o” in Bardo and “Arquero.”

Guille Estrujónez

Bill Huggins is one of our favorite trolls. His surname is of particular interest; in the translation, we find the Spanish word “estrujón,” literally “squeeze/press” or “bear hug.” There are two aspects to this translation: first, if we take the “bear hug” approach, then you will notice how “hug” is also present in his English surname (Huggins); and secondly, from the Spanish name one is immediately aware that this character must be strong and large.

Piedra del Arca

The Arkenstone can be interpreted many ways in Spanish. “Arca” can refer to a chest (as in of treasure) or to an ark (as in Noah’s). Either translation lends an antiquarian, more mystical nature to the stone.

In Spanish, the Shire is known rather literally as a “region” or “province”. This name was translated out of necessity, for in Spanish the “sh” sound does not typically exist. Personally, I find this name lacking of the novelty of “Shire.”

Bolsón Cerrado

The Spanish name for “Bag End” is rather odd. We find Bilbo’s surname used to represent the “Bag” in his aforementioned smial, but where one expects to find “end” there is the Spanish “cerrado” (literally “closed”). I am at a loss as to how to properly account for his translation; I will note, however, that the name flows much better as translated than if any variant of “end” had been used instead.

Montañas Nubladas

I find the Spanish name for the Misty Mountains very descriptive. Of note here is “nubladas” (literally, “cloudy/overcast”, from “nube” cloud). While “misty” and “cloudy” both denote mystery, the Spanish name is particularly foreboding; the verb “nublar” means “to darken/to cloud” and has a negative and ominous connotation in Spanish. This is of course an apt warning of the Misty Mountains.

Lago Largo

The Spanish version of the “Long Lake” is very evocative of its English translation. Both exhibit an alliterative nature and are composed of two one-syllable words. This is, perhaps, exemplary of an ideal translation, if ever there were such a thing, as neither an ounce of meaning nor sound is lost.

————————————————————————————–

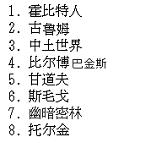

Next I present some Chinese translations of proper names.

Before continuing, however, I must note a few important characteristics of the Chinese language for those who have no experience with it. Unlike Spanish, Chinese is much more concerned with the preservation of sound. The Chinese have a long tradition of translating words such that they are phonetically similar to their native language-form. Here are two examples: first, the Chinese name for Germany is deguo (de, because of the German Deutschland, and guo meaning “country/nation”). While the character de has literal meaning (“virtues” or “ethics”), in this context it is used simply because it sounds like the “de” in Deutschland. Another example is the translation of the English name Michael; the Chinese form, maike, literally means something along the lines of “overcome wheat”. Yet, again, the Chinese in this instance forgo meaning in favor of sound. Thus, as you will see, the majority of translations involve preserving sound in Chinese. Yet looking at what potential literal translations of the names yield is a rather funny and interesting task.

This is the Chinese form of “hobbit.” It can literally be translated as “quickly compare special people.” This name, oddly enough, recognizes one truth: the unique and special nature of hobbits. Whether conveyance of this meaning was intended or not by the translator, I am not sure, though.

#2 (gu lu mu)

As you might have guessed, this is Gollum in Chinese. The literal meaning of this name is very odd: it can be translated as “nanny guru.” It does imply Gollum is old (which is true) and beholding of some secret knowledge, as a guru is (also, perhaps, true).

#3 (zhong tu shi jie)

The Chinese name for Middle-earth is an example where meaning is carried over sound. It literally means “middle earth/soil world”. However, another translation of “zhong1 tu3” is “Sino-Turkish,” though, of course, that is not the intended meaning.

#4 (bierbo bajinsi)

This is Bilbo Baggins—and a very difficult name to translate, too. The first name cannot really be translated at all. However, the surname is quite interesting; one translation could be “long for gold” which, although perhaps not applicable to Bilbo himself, is a rather pertinent note on the story as a whole.

#5 (gan dao fu)

As it sounds, this is Gandalf. The translation I like most for his name is “willing path man,” for, as we know, Gandalf is an instinctive wanderer; they do call him The Grey Pilgrim, after all.

#6 (si mao ge)

Smaug’s name is also very apt for his character. I translate this name as “careless spear,” which reflects his wantonly destructive nature.

#7 (you an mi lin)

The Chinese form of Mirkwood is another rare instance where meaning is favored over sound. This name literally means “gloomy jungle.” The dark and ominous connotation of the Chinese form is, in my opinion, much more powerfully negative than even the original English.

Lastly, I decided to include Tolkien’s Chinese name because it is oddly appropriate for the Professor. The name can be translated as “entrusting you with gold,” which I interpret in two ways: first, this can be seen as a reference to The One Ring, and, second, it can refer to Tolkien’s gift of his writings to us (his literary “gold,” if you will). Again, any intent on the part of the translator is impossible to know.

————————————————————————————

…. stay tuned for more from Tedoras ….

Join us every Tuesday for more engaging conversation with live chatters around the world who join our innovative broadcast TORn TUESDAY, featuring interviews with Tolkien/Fantasy luminaries, authors, and artists — many of whom are Ringer fans just like us! Every Tuesday at 5:00PM Pacific Time