If you’ve been around TheOneRing.net for a while… correction: if you’ve been around TheOneRing.net for a really, really long time, you might remember the section of our site called GreenBooks. GreenBooks’ tag-line was: Exploring the Words and Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien, and that’s exactly what our staff and guest contributors did there for many years. Sections included Quickbeam’s Out on a Limb, Turgon’s Bookshelf, Anwyn’s Counterpoint, and others, and explored topics on everything Tolkien with some movie and Peter Jackson articles thrown in for good measure.

If you’ve been around TheOneRing.net for a while… correction: if you’ve been around TheOneRing.net for a really, really long time, you might remember the section of our site called GreenBooks. GreenBooks’ tag-line was: Exploring the Words and Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien, and that’s exactly what our staff and guest contributors did there for many years. Sections included Quickbeam’s Out on a Limb, Turgon’s Bookshelf, Anwyn’s Counterpoint, and others, and explored topics on everything Tolkien with some movie and Peter Jackson articles thrown in for good measure.

Unfortunately, the old TORn site crashed early in 2007, which turned out to be a good thing as it forced us into the 21st century, adopting a new format that allows our readers to comment directly to articles (what a concept). However, GreenBooks became relegated to our old archived site, and the cobwebs grew thick there. Some of us oldies who know the right paths to take, still delight in poking around the old place every now and then, and while doing so recently it occurred to me that there’s no reason to leave such literary gems languishing in the cobwebs. So, once a week or so, I thought I’d dust one off and re-post it.

The one I selected for this week is titled: “Justice, Mercy and Redemption” by staff member, and co-author of TheOneRing.net’s books: “The People’s Guide to J.R.R. Tolkien,” and “More People’s Guide to J.R.R. Tolkien,” Anwyn. Also, if you’d like to take a peek, the old GreenBooks section is here. If you find something of interest that you’d like to discuss in this weekly feature, shoot me an email at altaira@theonering.net and I’ll put it towards the top of the queue.

Enjoy!

ANWYN’S COUNTERPOINT:

Justice, Mercy and Redemption

So how is it that Tolkien can get away with painting things this black and white? Don’t evildoers sometimes think better of themselves and mend their ways? Don’t good people fall? Sure they do.

It’s true. Tolkien doesn’t favor us with any clear-cut examples, at least not in Lord of the Rings, of people who were severe, lifelong evildoers and came to see the errors in their thinking (see Return of the Jedi for the best example of this, in Darth Vader), but he does provide us with several prime examples of justice, mercy, and redemption of those who fell to momentary or longer-lasting temptation.

We’ll define justice here as “the direct consequences of actions,” be they good or bad actions. We’ve all heard people whine “it’s not fair.” Well, fair is for late summer and 4-H. Justice is what happens, or should happen, in the real world. Justice is a failing grade for somebody who cheats on a test. Fairness is making sure that everybody else who cheats will also fail, but the justice, the failing grade, is the direct consequence of the action, the cheating. What about mercy? Well. To continue our line of thought, the cheating student has never done it before, swears up and down he will never do it again, begs for mercy, sits for a second, much harder, “for him only,” exam, and keeps the grade he gets on that one instead of the F he would have made for cheating. And redemption? That’s if the student studies his keester off and makes an A on the much harder second exam. And on a final note, there is no mercy for the student who is caught cheating more than once. Justice, for him, is the failing grade, without hope of clemency.

All right, Anwyn, how does your teacher mentality apply to Prof. Tolkien? It’s simple. Boromir lost the first round. He fell to sudden temptation to gain the Ring for his own, and tried to take it from Frodo by force. He recovered himself, was appalled at his behavior, begged for mercy, was given a much harder trial. He was killed, yes. But he was killed in defense of the Good, not in pursuit of the Evil, as we will see later in the cases of Saruman and Denethor. He passed the exam with flying colors. His spirit was redeemed. Tolkien tells us this in no uncertain terms.

“I tried to take the Ring from Frodo . . . I am sorry. I have paid.” His glance strayed to his fallen enemies; twenty at least were there. . . . “Farewell, Aragorn! Go to Minas Tirith and save my people! I have failed.”

“I tried to take the Ring from Frodo . . . I am sorry. I have paid.” His glance strayed to his fallen enemies; twenty at least were there. . . . “Farewell, Aragorn! Go to Minas Tirith and save my people! I have failed.”

“No! said Aragorn,” taking his hand and kissing his brow. “You have conquered. Few have gained such a victory. Be at peace! Minas Tirith shall not fall!”

But Anwyn! If somebody recognizes that he was wrong, says he is sorry and promises not to do it again, then wouldn’t it be merciful to forgive him and go on? Perhaps, in a better world. But you parents and teachers out there know, when you let a kid get away with something once without consequence, what does he learn? Only that he can get away with it without punishment. And to gain redemption, you have to prove yourself, as Boromir did.

Boromir is our perfect example of all three elements: justice, mercy and redemption. Sadly, not everybody can or will be redeemed. Have you ever heard the expression, “You can’t help someone who doesn’t want to be helped?” My mother used to say that long before “You have to want to get better,” came into vogue with psychologists/ psychiatrists. Saruman and Denethor were two very good examples of people who fell to temptation, fell into evil for however long or short a time, and who refused to recognize that they were at fault, refused to take responsibility or consequences for their evil actions. Now before I go on with this, I should mention a very nice, intelligent discussion I had with a reader who objected to Denethor being on my ‘villains’ list. His argument was that Denethor was overborne by the power of the Palantir, and through it, by Sauron, and so was not in his right mind at the end when he ordered his son’s death and had himself burned alive. Well. I will go so far to say that it seems likely Denethor was indeed out of his mind at that stage, but long before that, he had every opportunity to cease the use of the Palantir. Tolkien gives us evidence of the fact that he was addicted to using it. Very possible, but addictions can be cured. Gandalf tells Pippin how to avoid the temptation.

“Trust me. If you feel an itch in your palms again, tell me of it! Such things can be cured. But anyway, my dear hobbit, don’t put a lump of rock under my elbow again!”

Had Denethor ever been able to unbend his pride long enough to trust somebody of ‘lower’ status than himself, even one of his sons, he might have been turned aside from his path of self-destruction. But ultimately, his overbearing pride was the evil that led to his downfall. Pride whispered that he could control the Palantir, that it would give him yet greater power, and pride shouted at the end of his life that he was still the Steward, still in control, never yield to anybody without the authority of the Steward. Pride also claimed that that authority was greater than it actually was. One of my favorite, but also one of the most heartbreaking passages in all of Tolkien, is Denethor’s defiance before his death, and it exhibits this pride and despair (despair, by the way, being an active state and also another form of evil):

Had Denethor ever been able to unbend his pride long enough to trust somebody of ‘lower’ status than himself, even one of his sons, he might have been turned aside from his path of self-destruction. But ultimately, his overbearing pride was the evil that led to his downfall. Pride whispered that he could control the Palantir, that it would give him yet greater power, and pride shouted at the end of his life that he was still the Steward, still in control, never yield to anybody without the authority of the Steward. Pride also claimed that that authority was greater than it actually was. One of my favorite, but also one of the most heartbreaking passages in all of Tolkien, is Denethor’s defiance before his death, and it exhibits this pride and despair (despair, by the way, being an active state and also another form of evil):

“Authority is not given to you, Steward of Gondor, to order the hour of your death,” answered Gandalf. “And only the heathen kings, under the domination of the Dark Power, did thus, slaying themselves in pride and despair, mudering their kin to ease their own death.” …

“But I say to thee, Gandalf Mithrandir, I will not be thy tool! I am Steward of the House of Anarion. I will not step down to be the dotard chamberlain of an upstart. Even were his claim proved to me, still he comes but of the line of Isildur. I will not bow to such a one, last of a ragged house long bereft of lordship and dignity.”

“What then would you have,” said Gandalf, “if your will could have its way?”

“I would have things as they were in all the days of my life,” answered Denethor, “and in the days of my longfathers before me: to be the Lord of this City in peace, and leave my chair to a son after me, who would be his own master and no wizard’s pupil. But if doom denies this to me, then I will have naught, neither life diminished, nor love halved, nor honour abated … but in this at least thou shalt not defy my will: to rule my own end.”

His will . . . and ultimately, yes, his own end. Justice was granted in return for his pride and despair: a horrible death, a spirit unredeemed, and a death in despair, without seeing the rise of the country that he claimed to love.

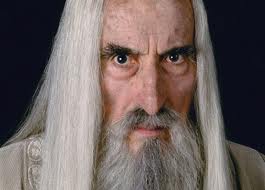

Saruman. Another almost heartbreaking case, one so knowledgable and formerly so wise, indeed a Maiar spirit, the equal of Gandalf whom we love and revere. What happened? A very similar story to Denethor’s, yet with a few noticable differences. Desire for power, for himself alone and not for the people under his rule; pride in his own accomplishments, not pride in the great nation over which he was given Stewardship; and conceit in thinking he was so much greater than his peers. Saruman was just a little more down-and-dirty with his evildoings. He covered it under a much thinner veneer. He made no secret, when he revealed his mind to Gandalf, of the fact that he wanted the Ruling Ring and was prepared to use force on whomever necessary to get it. But just as with Denethor, pride was the primary evil at work.

Saruman. Another almost heartbreaking case, one so knowledgable and formerly so wise, indeed a Maiar spirit, the equal of Gandalf whom we love and revere. What happened? A very similar story to Denethor’s, yet with a few noticable differences. Desire for power, for himself alone and not for the people under his rule; pride in his own accomplishments, not pride in the great nation over which he was given Stewardship; and conceit in thinking he was so much greater than his peers. Saruman was just a little more down-and-dirty with his evildoings. He covered it under a much thinner veneer. He made no secret, when he revealed his mind to Gandalf, of the fact that he wanted the Ruling Ring and was prepared to use force on whomever necessary to get it. But just as with Denethor, pride was the primary evil at work.

Those who will not receive mercy when it is offered are truly in dire straits. Mercy and redemption both were offered Saruman, but it would have meant casting aside his arrogance, ditching his hard-won ‘power,’ abandoning his machines and his tower, the symbols of that power. He simply could not admit that he had been wrong and that he ws now caught without any other way out.

“But listen, Saruman, for the last time! Will you not come down? Isengard has proved less strong than your hope and fancy made it. So may other things in which you still have trust. Would it not be well to leave it for a while? To turn to new things, perhaps? Think well, Saruman! Will you not come down?”

A shadow past over Saruman’s face; then it went deathly white. Before he could conceal it, they saw through the mask the anguish of a mind in doubt, loathing to stay and dreading to leave its refuge. For a second he hesitated, and no one breathed. Then he spoke, and his voice was shrill and cold. Pride and hate were conquering him.

“Will I come down?” he mocked. “Does an unarmed man come down to speak with robbers out of doors? …”

You get the point. It’s all in those two little words, ‘pride’ and ‘hate.’ In the very end, Tolkien seems to tell us again that Saruman’s spirit would have welcomed mercy if it were offered, but could not endure the harder test that would have redeemed him. Also it is worth noticing that the spirit seemed to waver this second time only after the body had been killed. In other words, when you have nothing left to lose, not even your life, sure, why NOT give up your evil ambitions and try to get back on the good side of the folks in charge? Unfortunately for Saruman’s spirit, there is no redemption for those who will not rise to the challenge of mercy.

“To the dismay of those that stood by, about the body of Saruman a grey mist gathered, and rising slowly to a great height like smoke from a fire, as a pale shrouded figure it loomed over the Hill. For a moment it wavered, looking to the West; but out of the West came a cold wind, and it bent away, and with a sigh dissolved into nothing.”

So. Justice comes to us all, be it a reward or be it consequences. (Justice for the Good will make a good topic for another time!) The decision is up to us on these things: will we give in to temptation, or not? And if we do, will we be able to cast down our evildoings, live up to the challenge of mercy, and be redeemed in the end?