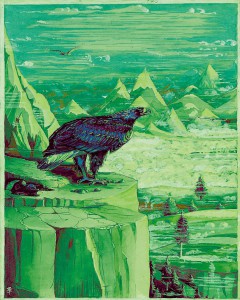

There’s always a great deal of amusement and comic humour to be derived from the Eagle-sized problem in The Lord of the Rings.

There’s always a great deal of amusement and comic humour to be derived from the Eagle-sized problem in The Lord of the Rings.

But as even newbie Tolkien readers understand: Eagles — they’re not a taxi service.

Of course, Tolkien himself was well-aware of the potential of Eagles to derail suspension of disbelief. Here, Benita J. Prins outlines just a few reasons why “one does not simply fly into Mordor”. (For a slightly different, but related, “you must earn your happy ending” perspective, I also recommend this feature by Gibbelins over on io9.)

One does not simply fly into Mordor

By Benita J. Prins

“Sure, The Lord of the Rings is a great story, but you have to admit that it does have a huge plot hole. Why didn’t they just fly on the Eagles into Mordor and drop the Ring into Mount Doom? That would’ve been so much easier, as well as quicker!”

This idea persistently pervades Tolkien fan communities all over the internet, and it is based on a misunderstanding of the reasons for forming a Fellowship — not to mention a very mistaken impression of the nature of the Eagles.

Now it is true that the Eagle idea conceivably could have worked. However, it would have greatly increased the risks of failure, and as we know, the possibility of failure could not be allowed for. Those at the Council of Elrond had to assume and plan for the worst-case scenario, not the best-case scenario, and for this reason the strategy of a Fellowship was the best solution. (It is important to notice that even here, the plan in its entirety failed; the Eagles could have quite plausibly failed as well.) Still, simply to walk into the Black Land, to sneak in ‘right under Sauron’s nose’ as the saying goes, would presumably work best; the most obvious often is the most successful since it is unexpected.

The mission to destroy the Ring depended on absolute secrecy, and to the Council, stealth was more important than speed. Eagles are far more noticeable than travellers on foot, especially Hobbits, who are skilled at stealth. Considering the presence of numerous “watchers” in Mordor — those at Cirith Ungol, and Orcs; even some birds were spies for Sauron — it is quite likely that an Eagle could easily have been taken down by the Nazgûl or archers. On the other hand, if on foot, one member of a company could scout ahead; they could sneak around, and hide swiftly…

A second reason why the Eagles would not have been a particularly good choice is that the birds could not have completed the mission by themselves. The Ring couldn’t be dropped just anywhere; it had to be put in the Crack of Doom itself, which was not out in the open but at the end of a tunnel into which an Eagle probably could not have fit. This then necessitates a rider to carry the Ring into the Sammath Naur. Having a rider, however, prevents flying high enough to be hidden by clouds, to ensure that the rider can breathe. It also would have crippled the Eagle during any possible fights it might have. Furthermore, an Eagle perched on Mount Doom would have been most conspicuous to any Orcs or minions nearby! A few people could sneak up the mountain with much less chance of observation.

Most importantly, we cannot just assume that Eagles would do whatever they were told. They were not slaves to be commanded at will, not a ‘convenience’(1). Rather, they were servants of the Valar, the ‘gods’ so to speak, and the Valar preferred not to interfere with Middle-earth’s problems(2). As Elrond states at the Council, “They who dwell beyond the Sea would not receive [the Ring]: for good or ill it belongs to Middle-earth; it is for us to still dwell here to deal with it.”(3) If the Valar would not receive the Ring or help to deal with the problem, then it is most likely that neither would the Eagles, their servants, have done so.

Finally, it should be remembered that, to Tolkien, the Eagles were in part a deus ex machina. This expression is defined as “a character or thing that suddenly enters the story…and solves a problem that had previously seemed impossible to solve.”(4) As Tolkien stated in one letter, “The intrusion achieves nothing but incredibility, and the staling of the device of the Eagles when at last they are really needed.”(5)

Thus we see that there are four great difficulties in sending the Eagles to Mordor with the Ring. The strategy would seriously impede the secrecy of the quest. A man would have to accompany the Eagle, hampering its safety and chances of reaching Mount Doom undetected. Eagles are not slaves but free beings, and furthermore, being servants of the Valar, are not apt to help the inhabitants of Middle-earth. Lastly, as a deus ex machina, their use should be kept to a minimum. Any one of these problems provides a compelling reason for telling someone who suggests the Eagle plot that “One does not simply fly into Mordor.”

Benita J. Prins is a writer from Ontario, Canada. She’s loved Tolkien’s works for years, and was inspired by The Lord of the Rings to write her first fantasy novel, Starscape, which will be published in 2015. She can be found online at www.benitajprins.wordpress.com.

Footnotes and works cited

1. They carried Thorin’s company to safety only because their King owed Gandalf a favour.

2. Cf. J.R.R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1977), p. 46.

3. J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring (London: Unwin-Hyman, 1954), p. 279.

4. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/deus%20ex%20machina, retrieved Jan. 13 2015

5. J.R.R. Tolkien, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, ed. Humphrey Carpenter, (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1995), p. 273.