Scarred by the horrors of the War of the Last Alliance

While not touched on in The Hobbit, Thranduil’s participation in the War of the Last Alliance is perhaps the single most influential event in his life. The horrors of the war (beyond the death of his revered father and the ravaging of his army) stuck with him long after victory was won. As the Third Age began, Thranduil and his folk felt a resurgence of fear and anxiety, an ominous air blowing from the East. While shadow and doubt slowly crept westward, Thranduil felt still a “deeper shadow” in his heart, for “he had seen the horror of Mordor and could not forget it” (UT 271).

While not touched on in The Hobbit, Thranduil’s participation in the War of the Last Alliance is perhaps the single most influential event in his life. The horrors of the war (beyond the death of his revered father and the ravaging of his army) stuck with him long after victory was won. As the Third Age began, Thranduil and his folk felt a resurgence of fear and anxiety, an ominous air blowing from the East. While shadow and doubt slowly crept westward, Thranduil felt still a “deeper shadow” in his heart, for “he had seen the horror of Mordor and could not forget it” (UT 271).

The pain of war remained very real for Thranduil, and “if ever he looked south its memory dimmed the light of the Sun” (UT 271). This sense of fear — a paralyzing, lasting dread — contrasts with the stern and proud king portrayed in the novel and on film. But for all his fear, Thranduil remained a wise and discerning leader; he understood the changes he felt in the world, and “fear spoke in his heart that [Mordor] was not conquered for ever” (UT 271).

Thus, when at last the Shadow reached the Woodland Realm, Thranduil led his people further north and east; and there, in a far corner of the Wood, they built and fortified great halls.

Interestingly, Thranduil took inspiration from another great Sinda before him, and, “following the example of King Thingol,” he delved underground, though his works rivaled not Menegroth of old (UT 272). It was indubitably a massive undertaking, but it serves to highlight this leader’s commitment to his people; for if there is one thing this delving conveys, it is a deep desire for peace, isolation, and security. Yet, for all their remarkable works and the ever-noble rule of Thranduil, the Silvan Elves of Mirkwood were still held as “rude and rustic” (UT 272).

Interestingly, Thranduil took inspiration from another great Sinda before him, and, “following the example of King Thingol,” he delved underground, though his works rivaled not Menegroth of old (UT 272). It was indubitably a massive undertaking, but it serves to highlight this leader’s commitment to his people; for if there is one thing this delving conveys, it is a deep desire for peace, isolation, and security. Yet, for all their remarkable works and the ever-noble rule of Thranduil, the Silvan Elves of Mirkwood were still held as “rude and rustic” (UT 272).

Their sundering from the rest of Elvendom goes beyond linguistic, geographic, and other cultural boundaries; rather, it is derived from a fundamental difference in worldview. Most importantly, the Silvan Elves of Mirkwood live with the inheritance of their Sindarin rulers, who “wished…to return…to the simple life natural to the Elves before the invitation of the Valar had disturbed it” (UT 272). It is a stark difference, and it runs straight to the core of the greatest internal struggle in Elvendom; yet, Thranduil and his folk give a firm, defiant answer, where others are far more subtle and cautious in their decision. But from a simplistic standpoint, the achievements of this group of Elves (and their lords Oropher and Thranduil, in particular) are all the more impressive.

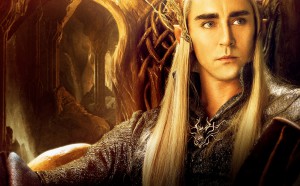

With the full history of Thranduil in mind, a rather different image of the King of Greenwood the Great emerges. Certainly, Thranduil is not given just treatment in The Hobbit: the noteworthy contributions of this valiant leader are, unfortunately, not noted. The Unfinished Tales provides great context for deeper understanding of this elf-king, but these are often overlooked by fans (though that work deserves as much scrutiny and focus as any).

The films have so far shown Thranduil in an expanded role, but he is as yet removed from the figure we have explored. As the third and final installment of the film series is prepared for release, we are left to wonder about Thranduil’s role. There is, of course, the Battle of Five Armies, but questions circle as to the fate of Dol Guldur (brought into the plot in film two), his relationship with Tauriel, and the portrayal of the final standoff post-battle.

Regardless, knowing more about Thranduil has me, at least, hoping that this Elf-lord will finally get some well-deserved attention.

References to the text from: Unfinished Tales by J.R.R. Tolkien, edited by Christopher Tolkien. Del Rey/Ballantine Books, 1988.

Tedoras is a bibliophile, linguist, and regular attendee at TORn’s live weekly webcast. He splits his time between scouring the web for Tolkien books to add to his collection and the study of Chinese politics and public policy.