And magic is not at all a supernatural phenomenon to this Elf; it is, rather, in his whole conception, a spatio-temporally-natural thing, being inspired by—and not distinct from—the world around him. Thus, we can add to Tolkien’s definition of love his own ideas on magic. This association between love and magic is also reinforced by Galadriel. At the Mirror, she tells Sam:

“‘And you?’ she said, turning to Sam. ‘For this is what your folk would call magic, I believe; though I do not understand clearly what they mean; and they seem to use the same word of the deceits of the Enemy’” (350).

Just as the aforementioned Elf, Galadriel cannot understand the hobbits’ loose use of the word “magic.” To her, it can only be linked to love, and works derived from love. She rejects wholly the notion that the term “magic” can be preferentially applied, that it is not as clearly a part of the noumenal realm to others as it is to her.

The distinction between the Enemy and those that oppose him is starkly framed in The Lord of the Rings; but, that it is a struggle between Love and Hate, beyond just Good and Evil, is manifested on a different textual level.

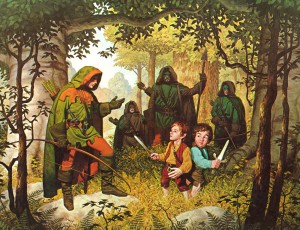

Fast forward a bit as we journey south now, to Ithilien. The young master Faramir is walking in the woods with his newfound halfling captives, his wisdom (clearly beyond his years) on full display:

“War must be, while we defend our lives against a destroyer who would devour all; but I do not love the bright sword for its sharpness, nor the arrow for its swiftness, nor the warrior for his glory. I love only that which they defend: the city of the Men of Numenor, and I would have her loved for her memory, her ancientry, her beauty, and her present wisdom” (656).

Whereas from hate the Enemy seeks to destroy, out of love Faramir seeks only to preserve. And yet another stark example comes to mind here. One of Aragorn’s very first tasks as King is to judge the fate of Beregond (who, if you remember, fended off to of his own in the service of the Citadel to prevent them from burning Faramir alive). Aragorn knows that, of old, the penalty for Beregond’s actions was death. However, what the King tells Beregond departs from this tradition:

“All penalty is remitted for your valour in battle, and still more because all that you did was for the love of the Lord Faramir. Nonetheless you must leave the Guard of the Citadel, and you must go forth from the City of Minas Tirith…So it must be, for you are appointed to the White Company, the Guard of Faramir…in the service of him for whom you risked all, to save him from death” (947-48).

How Aragorn’s decree relates to love is clear. But clearer still is another aspect of Tolkien’s multi-faceted definition of love, which is seen best through Beregond’s reaction as he, “perceiving the mercy and justice of the King, was glad, and kneeling kissed his hand, and departed in joy and content” (948). The Professor expounds (what he believes to be) the inherent righteousness of acts derived from or motivated by love. Certainly, Tolkien holds this notion very highly, for not only is Beregond not admonished for having killed a fellow countryman, he is rewarded by King Elessar.

All in all, it appears that Tolkien’s definition of love is truly complex. And while we can only postulate an exact definition (and such a definition can only remain conjectural), I believe the following is a safe guess: love entails a catharsis inspired or derived from beauty, existing either in nature itself or in human nature (where the principal catalysts are loyalty, trust, and mercy, amongst other interpersonal emotions).

Rather complicated, right? Well, I believe that if we wanted to simplify the aforementioned definition, the Professor would want us to remember this: even in Middle-earth (which is filled with Elves and dragons and wizards), love remains the true “magic.”

All references to the text from:

The Lord of the Rings by JRR Tolkien, single-volume edition, Houghton Mifflin

(HarperCollins), 2001 (1994 edition of the text)

Tedoras is a bibliophile, linguist, and regular attendee at TORn’s live weekly webcast. He splits his time between scouring the web for Tolkien books to add to his collection and the study of Chinese politics and public policy.