Tolkien for Nonbelievers

by Gibbelins

When I read Yann Martel’s recent bestseller Life of Pi, I was immediately repulsed by the preface, which asserts that the story “will make you believe in God.” I almost shut the book then and there. As a nonbeliever, I am naturally annoyed by anything that resembles proselytizing. But even if I were a believer, I would gag at the dull presumption of the claim.

The more humble Tolkien, though his enduring faith could never be doubted, would never have dared such a ridiculous and arrogant claim. He consistently rejected the urge to write overt religious allegory, so that one can easily read The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings without even realizing that they contain religious themes.

But as one delves deeper into the legendarium, it becomes increasingly difficult to ignore the deep-seated faith underlying the stories. Like the light that fills the Silmarils, faith in Tolkien is “within it and yet in all parts of it, and is its life” (67). Faith could never be extracted from the works and leave them whole.

Tolkien himself addressed it in a response to a fan letter:

“You speak of ‘a sanity and sanctity’ in the L.R. ‘which is a power in itself.’ I was deeply moved. Nothing of the kind had been said to me before. But by strange chance, just as I was beginning this letter, I had one from a man, who classified himself as ‘an unbeliever, or at best a man of belatedly and dimly dawning religious feeling…but you,’ he said, ‘create a world in which some sort of faith seems to be everywhere without a visible source, like light from an invisible lamp.’ I can only answer: ‘Of his own sanity, no man can securely judge. If sanctity inhabits his work or as a pervading light illumines it then it does not come from him but through him. And neither of you would perceive it in these terms unless it was with you also. Otherwise you would see and feel nothing, or (if some other spirit was present) you would be filled with contempt, nausea, hatred. ‘Leaves out of the elf-country, gah!’ ‘Lembas -– dust and ashes, we don’t eat that.’ ” (Letters, 413)

I at least do not spit out the sacred bread in disgust. Well do I perceive the sanctity of Tolkien’s world and feel its draw. Yet I cannot share his faith.

Often I have struggled with this inherent clash of sentiments. I wonder if my worldview is ultimately incompatible with my love for Tolkien, and if it is, what that ought to mean for me. I would consider it nearly impossible to maintain a romantic relationship with a religious person; why do I find it acceptable to maintain such an intimate emotional relationship with these deeply religious stories?

In one sense, the conflict is easily dealt with. I can say to myself: My understanding of the workings of Arda is instilled with a sense of ‘Secondary Belief’, as Tolkien would put it, but my understanding of the ‘Primary World’ is quite distinct and unchanged.

Moreover, if you have no personal sense of faith, is it even possible to grok Tolkien? Gazing into darkness and oblivion, can you truly grasp the sense of light and hope that Tolkien offers you?

I would venture to suggest that you can. One of the greatest tricks of Tolkien’s legendarium is that it completely separates faith from any particular dogma or institution. There is no trace of Catholicism in the faith that allows Frodo to walk into Mordor; it is a purer and nobler kind of faith.

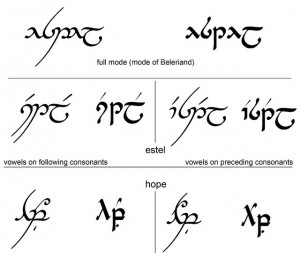

That faith is more a kind of “hope”, a trust in something both within yourself and larger than yourself, as illuminated by this conversation from Morgoth’s Ring, Volume X of The History of Middle-earth:

‘We look for no Arda Remade: darkness lies before us, into which we stare in vain’ [said Andreth, a mortal woman].

‘Have ye then no hope?’ said Finrod.

‘What is hope?’ she said. ‘An expectation of good, which though uncertain has some foundation in what is known? Then we have none.’

‘That is one thing that Men call “hope”,’ said Finrod. ‘Amdir we call it, “looking up”. But there is another which is founded deeper. Estel we call it, that is “trust”. It is not defeated by the ways of the world, for it does not come from experience, but from our nature and first being.’

The trust that Finrod speaks of would seem to be indispensable in any world. If, like Andreth, you feel that you are staring into the darkness in vain, how can you fight despair without some kind of hope? Whether you place your trust in humanity, in science, in art, in love, in God, or in something you cannot define, you need to trust in something. Or so I believe.

Tolkien’s ever-present faith has never been confined to Middle-earth. On clear nights we too may raise our eyes to the evening star, the first light in the darkness and the herald of the dawn, and dare to hope for better worlds.

Gibbelins is a librarian with a degree in linguistics and an abiding love for Tolkien. You can read more of Gibbelins’ features on Tolkien topics over on the io9 observation deck.