It’s easy to forget just what a feat it was to bring Tolkien to the screen at all, imbued not only with plausibility, but also mass appeal. We’ve become used to the idea that three foot six inch tall Hobbits can be relatable heroes, that four foot five inch Dwarves can be fearsome warriors, and wizards with pointy hats can have gravitas. This was not always so. I distinctly remember feeling a tension, as the lights dimmed in a Montreal movie theatre on 19 December 2001: as a Tolkien aficionado, I was terrified the first sighting of Frodo, or Gandalf, would elicit guffaws of derision from the uninitiated in the audience. Eleven years on, we tend to forget just how much of the Fellowship of the Ring’s acclaim was for its ability to make fantasy work at all. The Hobbit is just as remarkable a feat, yet because we know it has been achieved before, it’s inevitable it won’t be given its due. Jackson is competing against himself, without the advantage of true originality that the original films had in spades by dint of coming first.

The new film also suffers from déjà vu, and not simply in the return of a number of characters from the original trilogy. The journey taken largely matches that in Fellowship: it begins in Hobbiton, travels via the Trollshaws, stops in Rivendell for a Council, and then climbs up the Misty Mountains (in a storm, no less), before descending beneath them (where Goblins are encountered), only to climax in a battle in a forest with large orcs. The parallels are clear to anyone who has seen The Fellowship of the Ring. This is a problem about which the filmmakers can do little, for it is what Tolkien wrote.

What’s more, The Hobbit is a book that is virtually unfilmable. This is largely because it was written in 1937, in an era when a writer would have been far less influenced (if influenced at all) by the tropes, structures and cliches of film, things that inform the very fabric of more modern works of fantasy, from Harry Potter to Game of Thrones, where the writers seem to be writing a story that they are watching on a big screen in their imaginations. Tolkien, by contrast, lingers on whimsy, riddles, idiosyncratic dialogues, and gives little focus to action and adventure. This approach represents a challenge to a film adaptation for three main reasons.

A formidable challenge to adapt…

First, whereas The Lord of the Rings had a central cast of nine, made up of multiple races, The Hobbit is lumbered with a core male cast of 15. Thirteen of these are of the same race, short, bearded, and — by human standards — ugly. Such a huge and undifferentiated group of protagonists was always going to present a problem for adaptation, and was the main reason why Jackson was so reluctant to take it on in the first place. Many reviews of the new film have noted how the Dwarves remain undeveloped and impossible to tell apart. Yet this is actually in keeping with the book, where few of them are given distinct personalities. There is no need to foreground them all in the story. They are, for the most part, Thorin’s retinue, and are treated as such.

First, whereas The Lord of the Rings had a central cast of nine, made up of multiple races, The Hobbit is lumbered with a core male cast of 15. Thirteen of these are of the same race, short, bearded, and — by human standards — ugly. Such a huge and undifferentiated group of protagonists was always going to present a problem for adaptation, and was the main reason why Jackson was so reluctant to take it on in the first place. Many reviews of the new film have noted how the Dwarves remain undeveloped and impossible to tell apart. Yet this is actually in keeping with the book, where few of them are given distinct personalities. There is no need to foreground them all in the story. They are, for the most part, Thorin’s retinue, and are treated as such.

Second, the episodic nature of the story does not translate well to film, as it is, for the most part ‘one damn thing after another’, and lacks a clear antagonist throughout, let alone a deeper purpose, beyond reclaiming gold from a dragon. In light of this, it is entirely understandable that the filmmakers have taken liberties with the plot, creating a sub-plot involving Azog, who pursues the Company throughout the first film, and the broader context of the rise of the Necromancer.

(As an aside, the combination of these three things — its episodic nature, the need for clear antagonists to facilitate more immediate drama, and the need for a deeper purpose to give it a broader dramatic context — is what accounts for a trilogy of films. If the adaptation had been a single film, whole iconic episodes would have had to be excised; if it were two films, perhaps all could have been included, but their treatment would have had to be perfunctory, and there would have been little room for character development. Thus three films is understandable, and particularly as it allows the layering in of crucial dramatic tension, and for connective tissue to be inserted to align it with the original trilogy.)

Third, the book is full of what would appear, from a cinematic perspective, to be anti-climaxes. Gandalf’s dispatching of the trolls and the Great Goblin appears to be deus ex machina, as does the arrival of the eagles; Smaug is killed by Bard, a character who has not been previously introduced; the Battle of the Five Armies happens while Bilbo is unconscious.

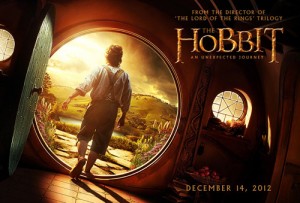

Bearing all this in mind — that Jackson is competing against himself and lacks the wild card of originality, in addition to dealing with a book that little lends itself to a screen adaptation — The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey is a triumph, albeit one that is bound to be perpetually under-appreciated.