Tolkien scholar John Garth reviews Tolkien’s long-awaited translation of Beowulf (together with the short story Sellic Spell) in The New Statesman.

Tolkien scholar John Garth reviews Tolkien’s long-awaited translation of Beowulf (together with the short story Sellic Spell) in The New Statesman.

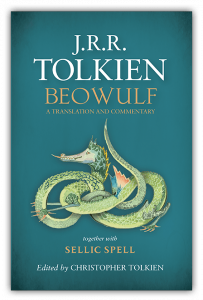

J R R Tolkien’s Beowulf: one man’s passion for the threshold between myth and reality

by John Garth

In his story “Leaf by Niggle”, J R R Tolkien imagines an artist painting a picture he can neither complete nor abandon. “It had begun with a leaf caught in the wind, and it became a tree; and the tree grew, sending out innumerable branches, and thrusting out the most fantastic roots.” In the end the picture is never put on show.

The metaphor captures the scale and gorgeous impracticality of Tolkien’s writing but not its fate. Most of his “tree” has been saved and his posthumous titles outnumber those published in his lifetime by roughly three to one. In this latest book, a deep root is exposed: his work on the Old English poem Beowulf. The surprise is how “fantastic” the root turns out to be, twisting thirstily through the scholarly subsoil to tap the groundwater of a forgotten folk tale – or “fairy story”, as Tolkien prefers to call it.

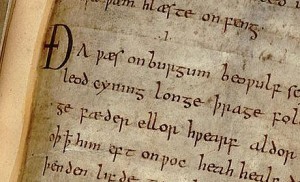

The poem, written down around 1000AD, mixes fiction with 5th- and 6th-century history. Beowulf sails from his Geatish homeland in Sweden to defeat Grendel, an ogre who has usurped the Danish feast hall of King Hrothgar. Beowulf then hunts down Grendel’s vengeful mother, but in old age, now king of the Geats, he slays and is slain by a dragon. In his 1936 lecture “Beowulf : the Monsters and the Critics”, Tolkien insisted that the poem is not just a mine for historical data into which some fantastical monsters have inconveniently strayed but a work of art in which the monsters are foils for an entire cultural attitude to life, death and courage.

The literary landscape has changed since then in a way that Tolkien would have neither expected nor accepted: he now towers in fame over Beowulf. Last year, Penguin repackaged its Michael Alexander translation as one of five “classic [stories] that inspired J R R Tolkien’s The Hobbit”.

The literary landscape has changed since then in a way that Tolkien would have neither expected nor accepted: he now towers in fame over Beowulf. Last year, Penguin repackaged its Michael Alexander translation as one of five “classic [stories] that inspired J R R Tolkien’s The Hobbit”.

Tolkien’s prose translation has been edited by his long-serving son Christopher, now 89, from versions dating back to 1926 (regrettably omitting an earlier, unfinished verse translation). A large, nuggety selection from Tolkien’s lectures, presented by way of commentary, ranges from semantics to genealogy, from the giants of Genesis to the Germanic concept of fate. Also included are two short, lapidary pieces of creative writing, “Sellic Spell” and “The Lay of Beowulf”. All this illuminates the poem but far more people will read the book for Tolkien’s sake than for Beowulf’s. That is fair enough.