WARNING: Spoilers for The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug and The Hobbit book.

The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug has drawn a lot of heat (see what I did there?) for deviating from the book. As stated in my review of the film, A Feast of Starlight, I have no problem with the new material and in fact, have enjoyed the depth and emotion the changes have brought to the story. However, the changes, and several fans’ resistance to them, have made me look at the story from an alternate view.

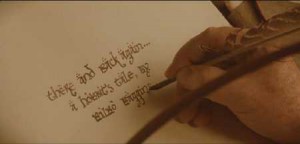

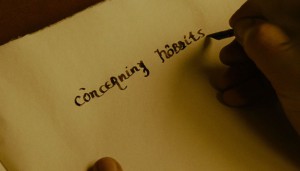

Bilbo starting the Red Book of Westmarch in Fellowship of the Ring, and Frodo nearly finishing it in Return of the King.

As a writer, one of the first things I must figure out when starting a book is the perspective. What best suits the story? First person? Present tense or past? Third person limited? Omniscient? Most of these considerations go unnoticed by readers, which is the point, for the mode of storytelling should never stand out more than the story itself lest you risk being perceived as a gimmick. One aspect of both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings that isn’t often brought up in respect to the films is one such choice Tolkien made: each book is written by a main character.

Frodo handing the Red Book over to Sam in Return of the King

Frodo handing the Red Book over to Sam in Return of the King

While I am not well-versed in Tolkien’s writing practices enough to know if his original intent for The Hobbit was for it to be told by Bilbo, it is made quite clear that by the time he wrote The Lord of the Rings, he had decided that each book would be written by Bilbo and Frodo respectively. Why both Baggins’ chose to write their accounts in third person is another matter, to say nothing of a non-Bilbo narrator occasionally addressing the reader in The Hobbit. This conceit is directly addressed in both film trilogies, most recently, of course, being Bilbo’s prologue in An Unexpected Journey where we see and hear him as he begins to record his tale.

Bilbo working on his book in Rivendell in Fellowship of the Ring

Bilbo working on his book in Rivendell in Fellowship of the Ring

As likewise established in the books, Bilbo begins work on his account (writing The Hobbit – the very book that you have read and loved!) a full sixty years after returning from his adventure with the Company. While sixty years may not be as large a portion of a hobbit’s life as it is a human’s, it is still a frightfully long span, and details would undoubtedly have been lost in the belated telling. Similarly, there would have been events that occurred in and around the Company of dwarves’ travels that the hobbit may not have been privy to.

This alone, from a storytelling and structural standpoint, is all the license the filmmakers needed to expand upon the text of the novel. You can either see Tauriel as an invented character, or simply as someone Bilbo had very little personal interaction with. After all, in The Desolation of Smaug, she is just one of the many Mirkwood elves to Bilbo’s eyes, and the two have next to no interaction. There is no evidence that he even knows her name.

Tauriel in Desolation of Smaug

Tauriel in Desolation of Smaug

As such, it stands to reason that Tauriel and nearly all she does could have been a key role in the Company’s adventure that Bilbo never wrote about because he wasn’t aware of her influence. Similarly, he would’ve been unaware of her friendship with Kili and how that bond and responsibility she feels for his fate is ultimately what drives her into leaving the borders of her land to help others.

Kili’s courage during the barrel escape and the splitting up of the dwarves at Laketown could be viewed as details forgotten by Bilbo, or deemed distractions from his narrative, for they would have been ultimately overshadowed by Kili’s sacrifice in the Battle of Five Armies. Similarly, the fact that some of the dwarves were split up on the journey is secondary to the fact they were all reunited again for the battle. Thorin’s attempts to kill Smuag while still within the mountain could have been blurred over time in Bilbo’s mind, for they were harried and ultimately failures in the face of Bard’s success.

It is fun to imagine that what we’re seeing on screen is the fleshed-out “reality” of the Company’s adventures rather than the (possibly limited) account Bilbo gives us over half a century after the events. How seriously Tolkien intended readers to interpret his words as Bilbo’s is unclear, however, the possibilities of opening the story up to influences outside of Bilbo’s knowledge is exciting.