On July 14 at this year’s Comic-Con, a thirteen-minute montage of clips from The Hobbit was shown during an appearance by Peter Jackson and cast members of the film. Afterward in press interviews, Jackson unexpectedly hinted that The Hobbit, long announced as being made in two parts to be released in December 2012 and 2013, might be expanded to three parts. This possibility inspired much skepticism among fans and members of the press. And yet only two weeks later, on July 30, it was announced that The Hobbit would indeed be released in three parts, the third to appear in the summer of 2014.

Although some fans of the film of The Lord of the Rings were delighted, there was much speculation in the press that the move was made from sheer greed, milking a third blockbuster from Tolkien’s modest children’s book. There were even some accusations that Jackson had lost his creativity and was seeking to extend his most successful series beyond its logical stopping point.

Yet if one reads the filmmakers’ statements about the decision to make an additional part of The Hobbit, it is clear that they intend to add more plot material rather than stretching the story of the relatively short novel. There is plenty of additional, directly relevant material in Tolkien’s appendices to LOTR. None of it is given in enough detail to make a free-standing film. Still, no doubt the filmmakers and the production studio began to realize that they had the rights to all this material, and that incorporating some of it into The Hobbit was their only chance to use it. Warner Bros. surely was delighted at the prospect of another lucrative blockbuster.

I’m not convinced, however, that Jackson’s team made their decision primarily from considerations of money. For one thing, some of the material from the appendices was created by Tolkien to tie the events of The Hobbit to those of LOTR. The filmmakers could use it for that same purpose. So far, the trailers and images from the forthcoming film seem to me quite promising in terms of how the appendices have been quarried for useful story items.

From two parts to three

I have a uniform paperback edition of the two novels where The Hobbit runs 272 pages and The Lord of the Rings, not counting the appendices or Prologue, runs 993 pages. So The Hobbit is less than a third the length of its sequel. The implication would seem to be that in order to be comparable to Jackson’s version of LOTR, its film adaptation should occupy a single part of perhaps three hours.

Of course LOTR, even in its eleven-and-a-half-hour extended DVD versions, left out a great deal of Tolkien’s novel. (Excision was Tolkien’s expressed preference, by the way, for a film adaptation. In a letter disapproving of a 1957 treatment for a proposed film of LOTR, he stated that cutting scenes was far preferable to racing through a complete but compressed version. See The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, p. 261.) Still, given the huge success of the three-part film, it seemed reasonable that Jackson and company would treat The Hobbit more fully, eliminating less and giving fans a more complete version of the earlier book.

But till, three parts for The Hobbit? Especially when this change was sprung on the public less than six months before the world premiere of the first part (November 28 in Wellington)? The move proved controversial and has been argued and speculated about ever since. Every trailer, every scrap of footage (especially the 13-minutes of clips shown at Comic-Con and still not available to anyone who was not in Hall H on July 14), every photograph has been closely examined for hints of what extra material might be included in an expanded Hobbit. (The Hobbit illustrations here are all from the second trailer.)

The reactions have generally been of four types. Keen fans of Jackson’s LOTR are delighted, trusting him and his fellow screenwriters, Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens, to come up with extra material true, if not to the book, at least to the spirit of the first film. Others are more skeptical, feeling that Jackson’s team is being too ambitious and is trying to stretch the book’s contents too far. After all, it was written as a children’s novel, not an epic romance like LOTR. A third group simply accuses Jackson of opportunism, whether his own or mandated by greedy corporate types at Warner Bros. (parent company of production unit New Line). Finally, a few commentators view the move as evidence of artistic “stagnation” on Jackson’s part

Most prominent among those in the fourth camp is James Russell, who wrote a piece baldly entitled “Peter Jackson’s three Hobbit films suggest he is running on empty,” for The Guardian. He argues that Jackson had never had a commercial success before LOTR, and that his post-LOTR films have been neither as lucrative nor as critically praised. Now, Russell suggests, Jackson has returned to familiar territory, despite having initially hired Guillermo del Toro to do the directing honors:

It’s hard to see how making The Hobbit could be seen as a positive step for Jackson. However, splitting the story into three separate films takes the moribund self-absorption of the project to entirely new levels. It looks as if Jackson is running entirely on empty, pushing this side project to ridiculous extremes because he has nothing else to offer.

(See also IndieWire‘s “An Open Letter to Peter Jackson on Splitting The Hobbit into Three Movies.”)

Jackson inadvertently encouraged such an interpretation back in the early days of pre-production, when del Toro was still the designated director. He said that he had visited Middle-earth once and did not want to compete with himself. Even when del Toro exited the project in late May, 2010, Jackson said he would not step into the job unless no one else could be found and the project was in danger of falling apart. Asked when the production process would move forward, he responded: “I just don’t know now until we get a new director. The key thing is that we don’t intend to shut the project down…We don’t intend to let this affect the progress. Everybody, including the studio, wants to see things carry on as per normal. The idea is to make it as smooth a transition as we can.”

The announcement that Jackson would in fact direct The Hobbit was not made until mid-October, and his statement in the press release was notably bland: “Exploring Tolkien’s Middle-earth goes way beyond a normal film-making experience. It’s an all-immersive journey into a very special place of imagination, beauty and drama. We’re looking forward to re-entering this wondrous world with Gandalf and Bilbo – and our friends at New Line Cinema, Warner Brothers and MGM.” Nevertheless, he has assured the public that once he agreed to direct, his immersion in pre-production re-ignited his enthusiasm for working with Tolkien’s material. Judging by the two trailers, as well as the video production diary entries so far posted on Jackson’s FaceBook page, that enthusiasm is genuine. The expansion of the film to three parts could be taken as another indicator that he has been inspired by his return to Middle-earth.

Not padding but extension

Major spoilers ahead! Page and chapter numbers from the two novels are from the most definitive versions of the texts: for The Hobbit, Douglas Anderson’s The Annotated Hobbit, second edition, and the 50th anniversary single-volume edition of LOTR, edited by Wayne Hammond and Christina Scull.

The widespread assumption since the announcement of the three-part Hobbit has been that Jackson and his fellow screenwriters would simply stretch out the action of the book. Yet that is clearly not what the trio is up to. In the press release, Jackson sounded much more enthusiastic:

Upon recently viewing a cut of the first film, and a chunk of the second, Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens and I were very pleased with the way the story was coming together. We recognized that the richness of the story of The Hobbit, as well as some of the related material in the appendices of The Lord of the Rings, gave rise to a simple question: do we tell more of the tale? And the answer from our perspective as filmmakers and fans was an unreserved ‘yes.’ We know the strength of our cast and of the characters they have brought to life. We know creatively how compelling and engaging the story can be and—lastly, and most importantly—we know how much of the tale of Bilbo Baggins, the Dwarves of Erebor, the rise of the Necromancer, and the Battle of Dol Guldur would remain untold if we did not fully realize this complex and wonderful adventure.

There is a great deal of material in the appendices of LOTR relating to the plot of The Hobbit, though in many cases that material involves characters and events barely referred to in the novel. In the book, Gandalf departs from the Dwarves and Bilbo midway through, going off, as he later reveals briefly “to a great council of the white wizards, masters of lore and good magic; and that they had at last driven the Necromancer from his dark hold in the south of Mirkwood” (p. 357). All this was later fleshed out, partly in the body of LOTR and partly in its appendices: the council became The White Council, which included Elves like Galadriel and Elrond; the Necromancer gained a name, Sauron; his “dark hold” became his secondary dark tower, Dol Guldur.

As is quite clear from the trailers and from statements by the filmmakers, action involving the White Council and the attack on Dol Guldur will figure prominently in The Hobbit. Already an image of the White Council, including Saruman and apparently taking place at Rivendell, has surfaced in one of the licensed tie-in books:

This may not, however, be the White Council meeting that occurs during the action of The Hobbit. It may be a flashback to the one in Third Age 2851, described in the invaluable chronology of Appendix B:

2850 Gandalf again enters Dol Guldur, and discovers that its master is indeed Sauron, who is gathering all the Rings and seeking for news of the One, and of Isildur’s Heir. He finds Thráin and receives the key of Erebor. Thráin dies in Dol Goldur.

2851 The White Council meets. Gandalf urges an attack on Dol Guldur. Saruman overrules him. (p. 1088)

An image of Dol Guldur appears in the second trailer:

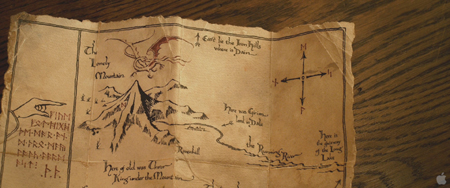

Saruman opposes the attack on Dol Guldur because he has secretly begun to search for the One Ring, desiring it for himself. Thráin gives Gandalf not only the key of Erebor but a map of it. That’s the map Gandalf looks at in Bag End just after his arrival in The Fellowship of the Ring. He will give the map and key to Thorin Oakenshield, son of Thráin and leader of the Dwarven troop in The Hobbit. Both will be crucial in the plot. The map also appears in the second trailer:

Tolkien wrote the appendices in 1954-55, vainly hoping to include them in the third volume of the novel. (They were incorporated into a later edition.) They retrospectively fill in events of the Third Age that led up to the plot of LOTR. He did not go back and extensively revise The Hobbit to incorporate these events, though he did a bit of fiddling with the original version in order to bring it more in line with LOTR. One cannot help but suspect that Tolkien wished he could have dealt with all these events in more than outline form. I for one am intrigued to see these bits of plot, sketched out by Tolkien in such a tantalizing way, fleshed out by the filmmakers.

No doubt that, as with LOTR, I will not agree with all the choices the screenwriters make in doing so. Still, we already have evidence that they can be adept in incorporating material from the appendices into the plot. They already did so to a more limited extent in LOTR. The scene in the extended DVD version of The Fellowship of the Ring of Aragorn visiting the grave of his mother, Gilraen, at Rivendell is derived from “Here Follows a Part of the Tale of Aragorn and Arwen,” a section of Appendix A (pp. 1057-1063). Tolkien considered this tale the most important part of the appendices, insisting that if foreign translations had to cut them, they should at least retain the narrative of the Aragorn-Arwen romance. The scene at Gilraen’s grave, brief though it is, adds depth to Aragorn’s character and to his relationship with his foster father, Elrond.

This moving story is also the source of the scene in The Two Towers where Elrond tries to persuade Arwen to leave Middle-earth for the Undying Lands by predicting her life with Aragorn. The dramatization of the prediction is a literal flashforward, for in the book Aragorn’s death eventually leads Arwen to regret her decision to remain with him, and she wanders, embittered and alone, in Lothlórien for a year before her own death (a period depicted by a single shot in the film). This flashforward is a powerful scene, and the film is all the better for its inclusion. We should not leap to the assumption that Jackson, Walsh, and Boyens will falter in their attempts to draw material from the appendices into The Hobbit.

There has been much fan speculation that the longer version of The Hobbit will include flashbacks to more of the Dwarves’ history. A scene might show the dragon Smaug driving the Dwarves from their ancestral home in the Lonely Mountain and assembling the hoard on which he lies when they return to retake the mountain. It might include their move into exile in the Blue Mountains west of the Shire. All of this could also be linked to Moria. Balin, whose tomb the Fellowship members discover in the Mines of Moria in The Fellowship of the Ring, is a character in The Hobbit, the eldest of the Dwarves. Between the action of The Hobbit and that of LOTR, he leads a troop of Dwarves to Moria to try and recapture it from the orcs that had conquered it generations earlier.

Tolkien wrote a brief history of the Dwarves and Khazad-dûm (Moria) in “Durin’s Folk,” another section of Appendix A. This includes an entire scene with dialogue, depicting Thráin’s father Thrór’s suicidal attempt to re-enter Moria; he is killed by the orc Azog. Although not crucial for the Quest of Erebor plot of The Hobbit, a flashback to such a scene would link it to the Moria passage of LOTR. There is a causal connection as well. Before departing for Moria, Thrór gives Thráin the last of the seven Dwarven rings, which leads Sauron to capture and imprison Thráin in Dol Guldur, taking the ring from him; that is why Gandalf later finds him in Sauron’s dungeons.

Such scenes might or might not be used, but the filmmakers have definitely decided to include Radagast the Brown, the third wizard, who is only mentioned in The Hobbit. (He appears in one scene in the LOTR novel, but he was eliminated from the film.) Radagast plays a limited role in Tolkien’s Legendarium, having apparently “gone rustic” and become absorbed with the birds and animals of Mirkwood, largely abandoning his part in trying to defeat Sauron. Still, his inclusion in the film seems a positive thing, as some charming shots of him playing with hedgehogs in the second trailer suggests:

The decision to divide The Hobbit into three parts presumably came too late to permit numerous changes in the first part. Nonetheless, the point at which the first film was planned to end has apparently been changed dramatically. The film’s official site posted an interactive wallpaper generator that showed a panoramic scroll summarizing the film’s scenes, from Gandalf scratching a rune on Bilbo’s door to the moment when the Dwarves and Bilbo escape from Thranduil’s dungeons in barrels floating down a river. That scene happens well over halfway through the novel. Once the three-part release was announced, the wallpaper generator was changed to its current version, which ends with the episode of Gandalf, the Dwarves, and Bilbo trapped up burning fir trees by wargs and goblins. Two shots from that episode are the latest events shown in the new trailer and would seem to provide a good cliff-hanger for the ending:

This episode happens in Chapter 6 of the book’s 19 chapters, while the barrels scene is in Chapter 9. This shift suggests that a considerable chunk of action has been added to the first film. That action probably derives from the LOTR appendices rather than some stretching of episodes from The Hobbit.

Perhaps to reassure fans, most of the second trailer shows scenes very familiar from the book: the Dwarves arriving unexpectedly at Bag End, the three trolls preparing to cook Bilbo (above), and of course the beginning of the famous riddling contest between Bilbo and Gollum. Two shots of Bilbo’s awestruck reaction to being in Rivendell (see the top) capture the spirit of the book perfectly. After all, Bilbo ended up living in Rivendell during his declining years, and while there he translated the ancient Elvish texts that became The Silmarillion. All this suggests that the bulk of the material derived from the appendices will appear in the second and third parts.

As a long-time Tolkien fan, I would be as disappointed as anyone if the decision to divide The Hobbit into three parts were done merely by stretching out the plot of the novel. All the evidence, however, points to a careful incorporation of bits of Tolkien’s own text to fill out the background of the tale and to link it more firmly to LOTR. Essentially it sounds as though the screenwriters have sought and probably found a way to incorporate the original “bridge” film, announced long ago when The Hobbit adaptation was first revealed in the press, into The Hobbit.

The bridge film was to have been a sequel to The Hobbit, which at that time was planned as a single film. It would fill in the events between the end of The Hobbit and the beginning of LOTR–a gap of sixty years in the novels. It apparently was to have been made up primarily of scraps of plot garnered from the appendices. Whether the writers would have been able to come up with an overall structure to unite those scraps is debatable. Using the strong spine of The Hobbit‘s plot to support them seems a promising solution to the problem.

Perhaps I will be disappointed upon seeing the film, but all the evidence so far indicates that the writers have been inventive and careful in expanding the project. Moreover, the trailers suggest that the technology used to create Gollum and to manipulate the sizes of the actors has improved since LOTR, as the frame below indicates. The recent confirmation that the first part of The Hobbit will run two hours and 44 minutes, sixteen minutes shorter than the theatrical version of The Fellowship of the Ring, also suggests that the division of the film into three parts isn’t being done through mere padding.