Gollum is an addict of the One Ring. Gollum identifies with the Ring, calling both himself and the Ring “my precious”. Gollum’s personality has been nearly destroyed by possessing and being possessed by the Ring for hundreds of years.

I think most readers of The Lord of the Rings would agree with these characteristic statements about Gollum. They explain his extraordinary behavior and bizarre speech patterns. The identity of Gollum with the Ring is one of the driving forces behind the primary plot of the book: Frodo’s quest of Mt. Doom to destroy the Ring, in which he is guided for much of the way by Gollum, who treacherously hopes to recover it for himself. Gollum’s degradation and tendency to evil also shows us the danger that Frodo is in. If he succumbs to the Ring, he will become another Gollum – who was, originally, a hobbit!

But who remembers Gollum from the good old days? Back when the Ring was just a ring. Back when Gollum was just a scary but funny ghoul who ate passers-by, but loved riddles. Back when he would abjectly apologize for breaking a promise, and ever so politely show his guest the way out of his cavern. Who now has read the first edition of The Hobbit, written years before The Lord of the Rings was even thought of? In that quaint book, Bilbo’s ring is truly just a ring of invisibility, introduced into the story to better his chances of success as the world’s most unlikely burglar. And Gollum, as described above, was a lot more innocent – a mere figure of passing comic-horror in the same league as the three Cockney trolls, and the cattily hissing spiders.

As Tolkien’s more scholarly fans know, he re-wrote the “Riddles in the Dark” chapter of The Hobbit in 1947, when The Lord of the Rings was completed. His purpose was to align Gollum and the Ring more closely with the radical new identities they had assumed in the forthcoming epic. So most Hobbit readers today are familiar with Gollum flying into a murderous rage when he discovers his Ring is missing; unwittingly leading Bilbo to the exit; forcing Bilbo to choose between killing Gollum or jumping over him; and crying in despair as Bilbo flees, “Thief! Baggins! We hates it forever!” There is even an obscure mention of “the Master who ruled [such rings]” – a tantalizing hint, but only to those who had read ahead.

All those foreshadowing moments were added in 1947 and published in 1951. But some of us have read the original book; or have read the original parts of the “Riddles” chapter in The Annotated Hobbit (by Douglas Anderson, 1988, rev. 2002). And I at least have puzzled over the riddle that most Tolkien commentators seem content to ignore, because it is so easy to ignore:

Gollum, precious

Rolls his esses –

Blesses, splashes,

Self-addresses.

Whence this creature’s

Precious features?

Remarkable thing:

It wasn’t the Ring.

In more prosaic terms, what was the original nature of Gollum’s distinctive personality, my preciousss… when there was no Ring?

To be sure, Gollum was always Gollum. From his opening line:

“Bless us and splash us, my precioussss! I guess it’s a choice feast; at least a tasty morsel it’d make us, gollum!”

to his recognition of Bilbo’s ability to defend himself:

“Praps ye sits here and chats with it a bitsy, my preciousss. It likes riddles, praps it does, does it?”

to his protest at Bilbo’s desperate last question:

“Not fair! not fair!” he hissed. “It isn’t fair, my precious, is it, to ask us what it’s got in its nassty little pocketses?” (all from The Hobbit, Chap. V, unchanged in the 1951 revision)

Gollum showed all his characteristic tics in the original 1937 text. He talks to himself (“he always spoke to himself through never having anyone else to speak to”). He never says “I”; it’s always “we” or “my precious” (“he always called himself ‘my precious’”). He lisps, or at least extends his sibilant “s” sounds (“preciousss” and “nassty”); in line with this, he redoubles his plurals (“pocketses”). His vocabulary is somewhat juvenile (“tasty”, “bitsy”, “it isn’t fair”).

Yet obviously, none of this was originally due to the influence of the One Ring!

And some things were different, at first. “My precious” referred to Gollum, only. The ring was separate. Compare the first edition text:

“Must we give it the thing, preciouss? Yess, we must! We must fetch it, preciouss, and give it the present we promised”…”Where iss it? Where iss it?” Bilbo heard him squeaking. “Lost, lost, my preciouss, lost, lost! Bless us and splash us! We haven’t the present we promised, and we haven’t even got it for ourselves.” (The Hobbit, Ch. V, 1937)

with the changes that Tolkien made after developing Gollum and the Ring in The Lord of the Rings:

“Did we say so, precious? Show the nassty little Baggins the way out, yes, yes. But what has it got in its pocketses, eh? Not string, precious, but not nothing. Oh no! gollum!”… “Where is it? Where iss it?” Bilbo heard him crying. “Losst it is, my precious, lost, lost! Curse us and crush us, my precious is lost!” (The Hobbit, Ch. V, 1951 and after)

In the first passage above, early-Gollum maintains a clear distinction between himself, “my precious”, and the ring as “the thing”, “the present” or just “it”. But at the climax of later-Gollum’s panic in the second passage, the ring as “it” suddenly becomes the Ring as “my precious”, which is the now-familiar convention of dissolved personality and Ring-enslavement which Tolkien had already developed to such powerful effect in his second book.

In short, to ascribe Gollum’s mode of speech to the power of the Ring is correct when analyzing The Lord of the Rings, and even The Hobbit as Tolkien rewrote it. But the Ring as such does not explain why Gollum originally spoke the way he did! To make the question more interesting, we can’t help but reflect that the change-over was very easy. Gollum’s distinctive personality and speech was seemingly ready-made to be transformed into an expression of the corrupting One Ring!

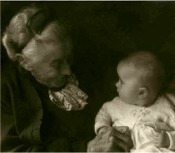

As I consider this paradox, I have been struck by the idea that early-Gollum has a feminine aspect – represented by his mincing lisping timidity and nursery-talk. I would like someday to spend more time researching the British vernacular terms Gollum uses, primarily “my precious”, “choice feast”, “tasty morsel”, “Praps ye sits here and chats with it a bitsy”, “Is it scrumptiously crunchable?”, “its nassty little pocketses”, “Bless us and splash us!” (used twice – oddly reminiscent of baptism; an English regionalism?), and “We durstn’t go with it, my preciouss, no we durstn’t, gollum!” (“dursn’t” is also used by Sam in Fellowship of the Ring – another regionalism?). Could these odd phrases and mannerisms of speech be a kind of baroque nursery-talk, such as a horrid old lady or nursemaid might coo over a baby?

“Baby-talk” is now called “Child-directed speech” (CDS), but we all know how it sounds. A fascinating testimony to its ancient origins can be found in a 1539 remark by John Calvin:

“God, in so speaking [as if He has human form], lisps with us as nurses are wont to do with their children.” (Institutes 1.13.1, trans. Beveridge, 2002.)

Along with Gollum’s childish lisping, consider his phrase “my precious”. As I noted above, it became in The Lord of the Rings a leitmotif for a fatal self-identification with the Ring. But it has long been a term of endearment for adults to use about little children, or for child-substitutes like pets, or even to impose a childish identity on a loved one. Here are some examples from the period of The Hobbit:

…pressing her cheek to Flopit’s, she changed her tone. “Izzum’s ickle heart a-beatin’ so floppity! Um’s own mumsy make ums all right, um’s p’eshus Flopit!” (Tarkington, B., 1917, Seventeen.)

… a few rounds of “Baby precious [Stein’s nickname for Toklas], oh dear baby so precious, sweet kissed baby so precious” will drive more than a few readers to distraction. (Publishers Weekly, 1999. Review of Baby Precious Always Shines: Selected Love Notes Between Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas.)

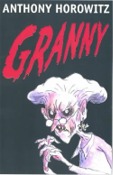

If we think of Gollum as a speaker of CDS, we may remember once more that this story began in part as a nursery tale, told at bedtime to small English children of the 1930s. Even in the original The Hobbit, Gollum was a ghoul and a monster, but he was a strangely endearing one because of his language. Isn’t it possible that Gollum’s original, pre-Ring personality was that of a nursemaid-turned-monster, to the thrilled horror of the Tolkien children? At the core of the caricature is a childless old lady who cannot let a precious infant go, but will continue to baby it, coddle it, spoil it, and dominate it, long after it is time to let the child grow up – and so she becomes the child, and the child becomes her.

Looked at this way, Tolkien’s satirical rendering of a pathologically self-infantilized child-creature relates very well to the story of Bilbo, a child-sized adult who rediscovers his lost but strong inner fantasy-child. The original Gollum, and Bilbo, have a monster-victim relationship that is most appropriate to The Hobbit with its strong theme of Childhood Lost and Regained – wherein Gollum is Childhood Endlessly Prolonged.

I would argue that with the appropriate pairing structure already in place, Tolkien easily translated the nursery-nightmare obsessiveness, schizoid self-reference, and perverted morality of The Hobbit’s early-Gollum into the Ring-consumed later-Gollum who so dominates The Lord of the Rings. In the new book he relates to a Ring-threatened Frodo in the same “unhealthy-healthy” paired way.

One can see the actual transformation in Book I, Chapter 2 of The Fellowship of the Ring, where Tolkien finesses a number of Gollum’s characteristics to match the needs of the new story. Once Gollum was a mysterious creature (“I don’t know who or what he was”); now he is “of hobbit-kind”. Gollum would never cheat at the ancient riddle-game; now Gollum “meant to cheat all the time”. He got the ring as a present in older times when magic rings were less uncommon; now this was revealed to be a guilty lie. Gollum’s distinctive mannerisms didn’t change, but his biography, actions, and motivation did.

Tolkien’s sleight-of-hand in The Lord of the Rings was helped greatly by the changes he had lately made to Gollum in The Hobbit. Readers and critics alike now seldom ask to see the cards from which our precious Gollum was conjured. This amazing re-use and re-invention of Gollum is Tolkien at his slippery best. As an inventor of story he never looked back. He stuck with his literary ideas – like the Ring, or Gollum – however primitive their origins, and developed them until their inherent genius finally came fully alive.

(This essay was adapted from a Reading Room post of April 27, 2009.)