“Ac se wonna hrefin | But the black raven

fus ofer fægum | eager over the doomed

fela reordian, | speaking many things

earne secgan | telling the eagle

hu him æt æte speow, | how he is succeeding in eating,

þenden he wið wulf | when he with the wolf

wæl reafode.” | despoiled the slain.

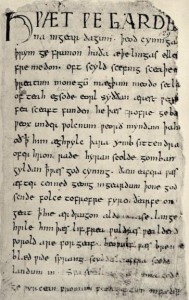

The Angle tribe brought Anglish to Angleland. See what our ancestors did there? It was in this changed England that a monk wrote down the story of Beowulf and hid it in the back of a book full of Christian tales, hoping that it would escape any sort of religious purge.

For years, the poem wasn’t given the scholarly attention it was due, until a professor in Oxford named J.R.R. Tolkien wrote a paper called “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics,” arguing the poem’s significance.

He also translated the poem himself in 1926. Until now, that translation has not been accessible to the public. With guidance from Tolkien’s son, Christopher, the professor’s translation is being published.

This is huge news to Old English scholars, for Tolkien is considered a banner-bearer for the language and his efforts to restore Beowulf to its rightful place in English literature are revered. My first exposure to the poem was junior high where I delighted in the story, but it was Tolkien’s influence that prompted me to actually take a course studying Old English in college.

One of my favorite parts about translating the poem was the fact that we do not have a complete manuscript, nor a complete lexicon. These words of unknown significance and blank patches in the story fueled Tolkien’s imagination.

For example, Earendil is one such Anglo-Saxon word for which we have no meaning but Tolkien used in Lord of the Rings as the name of an Elvish star. The professor gleefully gleaned so much from the text that I can’t wait to read his translation and see what else he discovered.

The above quote, selected randomly from my stacks of paper that are my novice Beowulf translation, is a perfect example. It’s not hard to see where the idea of the talking birds that we meet in The Hobbit could have come from.

For more on Tolkien’s translation, head over to The Guardian’s article here.

And if you’re curious and would like to know more about Old English, I can highly recommend the site Beowulf on Steorarume, or Beowulf in Cyberspace 😉